Historical Photos by R.L.K. & Company

Snowboarding at Mt. Hood has been the go-to summer destination for 30-plus years now. It’s so much a part of the culture and history of our sport, that it’s likely you never thought much beyond your own immediate experience of shredding the Palmer snowfield, hanging out in Govy, skating the ramps and partying at Charlie’s. But you should know, there’s a lot of history here and it’s pretty damn interesting.

First things first, about the mountain. Mt. Hood is a long-lived active volcano with a geologic history going back over a million years. Its last major eruption occurred in the 1780s not long before Lewis and Clark’s expedition to the Pacific Northwest. The mountain is dotted with fumaroles—holes in the snow where hot lava rocks emit toxic sulfur dioxide and other gasses. You’ve most likely gotten a whiff of sulfur as you ride along the cat track off the top of the Palmer lift.

Looking out from that cat track, you see trees and lakes and wilderness—these are the ancestral lands of almost 100 diverse bands and tribes of indigenous people who lived in the region before colonization. To the west are tribal communities including the Willamette, Clackamas, Molalla, Multnomah, Watlala, Chinook, Salish, Kathlemet, Tualatin, Kalapuya, and many more who today are part of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. To the east are the tribal communities of Warm Springs, Wasco, Piute, Tenino, Wishram, and more of the high desert and Columbia River, known as the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. The land on which we recreate historically belonged to these native and indigenous people.

Wy’East was the historical native name for Mt. Hood. In 1792 the mountain was renamed after Lord Hood—a British admiral who fought against the American colonies in the Revolutionary War. There’s talk of changing the name back to Wy’East—this would be like Alaska’s Mt. McKinley renamed to its native name, Denali, not unheard of.

Native peoples historically stayed on the slopes and valleys, as the summit was considered a sacred place. It wasn’t until the 1900s that Portlanders, many affiliated with the Mazamas climbing club, began traveling south to climb and ski Mt. Hood. The destination back then was the starkly named town of Government Camp, aka “Govy.” The name dates to the mid-1800s when an army regiment abandoned wagons and supplies in heavy snow. Govy was the original skiing and ski jumping destination in the late 1920s, with ski jumps at Multorpor/Ski Bowl, a rope tow at Summit Ski Area, and other uphill contraptions created by the ski clubs, including Cascade Ski Club (the onetime home of High Cascade Snowboard Camp), which drew adventurous skiers to its slopes. Back then, it was the last bit of civilization below the towering summit of Mt. Hood.

Timberline Lodge & Ski Area

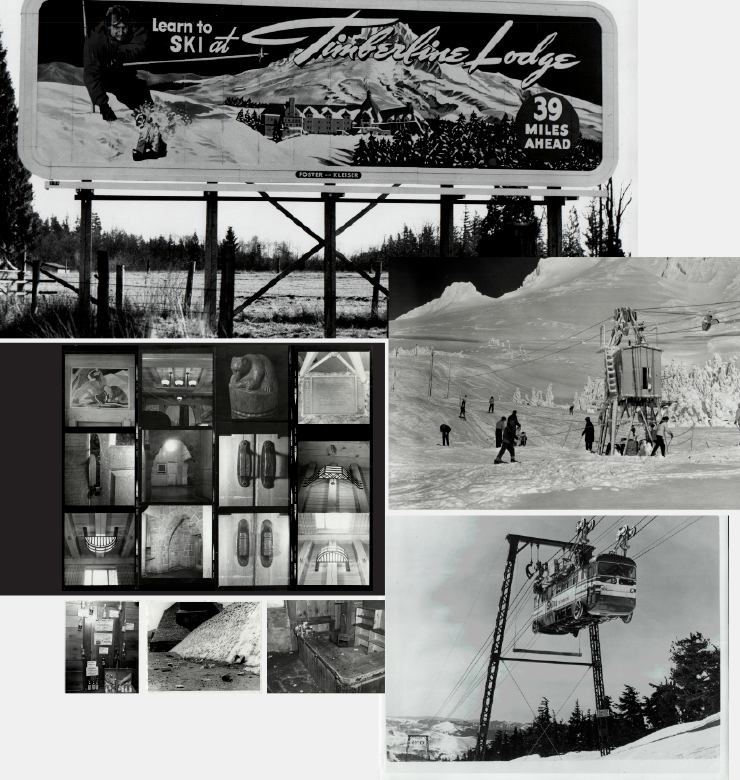

Timberline Lodge and the road winding up to it were built as part of the New Deal, following the Great Depression, and completed 85 years ago, in 1937. President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself dedicated it, standing on the small porch looking out toward Mt. Jefferson. The interior is a monument to American arts and crafts, featuring animal carvings, metalworks, tapestries, and majestic river rock fireplaces with history is imbued into every square inch of the lodge. The lodge sits at the base of Palmer Snowfield, and the name Timberline denotes the fact that, at 6,000 feet, it’s located at the point where the forest gives way to the high alpine—the timber line.

Skiing and climbing were always a lure of the lodge. Early visitors jerry-rigged a toboggan surface-lift to ski laps nearby; it was also common for visitors to ski down to Govy and catch a ride back up to the lodge. Then, in 1939, the Magic Mile roared into operation. It was only the second ski lift in North America (the first at Sun Valley in 1936) and the longest. The diesel-powered single chair lift was 4,950-feet long, ascending 991-feet to Silcox Hut, a warming hut and starting point for climbers, located a mile above the lodge. Timberline Lodge was popular, but not remotely profitable in the early years, and then WWII came. The lodge closed in 1942 for three years, as the war raged and gas was rationed, reopening in 1945 in disrepair. Nonetheless, the skiers flocked.

Management of the resort changed hands repeatedly as operators struggled to turn a profit and keep up with maintenance. With changes in management, the vibe of the lodge also started to change. In 1950, the then dry lodge added the Ram’s Head Bar to the upper mezzanine. The operator at the time surreptitiously introduced unlicensed gambling to the lodge activities—according to a passage in the book Timberline Lodge, in 1953 a forest service ranger discovered a blackjack table and portable bar in room 301, with unlicensed slot machines installed in the bar. The ranger also discovered other “activities that the forest service preferred not to discuss” at the lodge. Use your imagination.

It got worse before it got better. In late 1953, a decidedly sketchy Portland businessman named Charles Slaney took over the lease. As described in a 1956 Sports

Illustrated article, “The lodge and the skiing area fell into total disrepair. When the 1954 season began, none of the usual preparations had been made for winter. The chair lift was out of order, the rope tow was buried in snow, dirt and broken equipment piled up in the kitchen, lounges and rooms.” The forest service gave Slaney the boot in January of 1955.

This could have been the end of the Timberline Lodge, and the development of a ski area on Mt. Hood, but this story has a hero and his name is Richard “R.L.” Kohnstamm.

In the winter of 1955, Kohnstamm, a social worker originally from New York, with a background of working at summer camps and skiing at Mt. Hood, took over the lease at just 29 years old. Kohnstamm had served as a gunner during the war, where he was part of the occupying forces in Munich, Germany. He returned to Europe following the war to visit ski resorts that were operating year-round on glaciers. He saw the success of summer skiing there and found inspiration to open Timberline to summer access.

But first, there was the immediate and huge task of cleaning up the lodge—which was a fire hazard and a “bust” as they said in those times. There was a broken bullwheel near Silcox Hut, stolen, broken and burned furnishings, a lodge so utterly destroyed that there was talk of tearing it down. Kohnstamm rolled up his sleeves and got to work, in the process putting himself into debt with renovations and restorations. The same story in Sports Illustrated offered an overview of how things were as skiing ramped up again, “The resort was patronized by upwards of 90,000 skiers each year, from 50-cents-per-lunch youngsters to $33-a-day luxury guests.” Visitors were back at the lodge, this time for skiing instead of gambling.

Timberline Today

You’ve probably walked past the lodge many times. You should go in. There are cool displays of the early days, incredible pictures on the walls, even a small documentary film theater just past the main lobby looping a film detailing the lodge’s construction. You can also wander upstairs to the Ram’s Head for a late lunch or cocktails, and, if it’s open, slide into the Blue Ox Bar—a tiny stone-walled lounge behind an iron gate that you have to find down a distant corridor. Go ahead and book a room and stay the night for the full experience. There’s night riding and wood-burning fireplaces in the rooms and a heated outdoor pool. Notably, Timberline Lodge is the only slopeside ski-in-ski-out lodge in the entire state of Oregon.

Bonus points if you watch The Shining during your stay, which famously features the exterior of the lodge as the setting of the iconic Kubrick film. Another viewing choice is All The Young Men, a Korean War film shot on the mountain in 1960—it’s said that the profits made from accommodating the film crew basically turned the finances of the lodge around, saving Kohnstamm and the lodge.

Summer Camps At Hood: Ski Racing Leads to a Snowboard Takeover

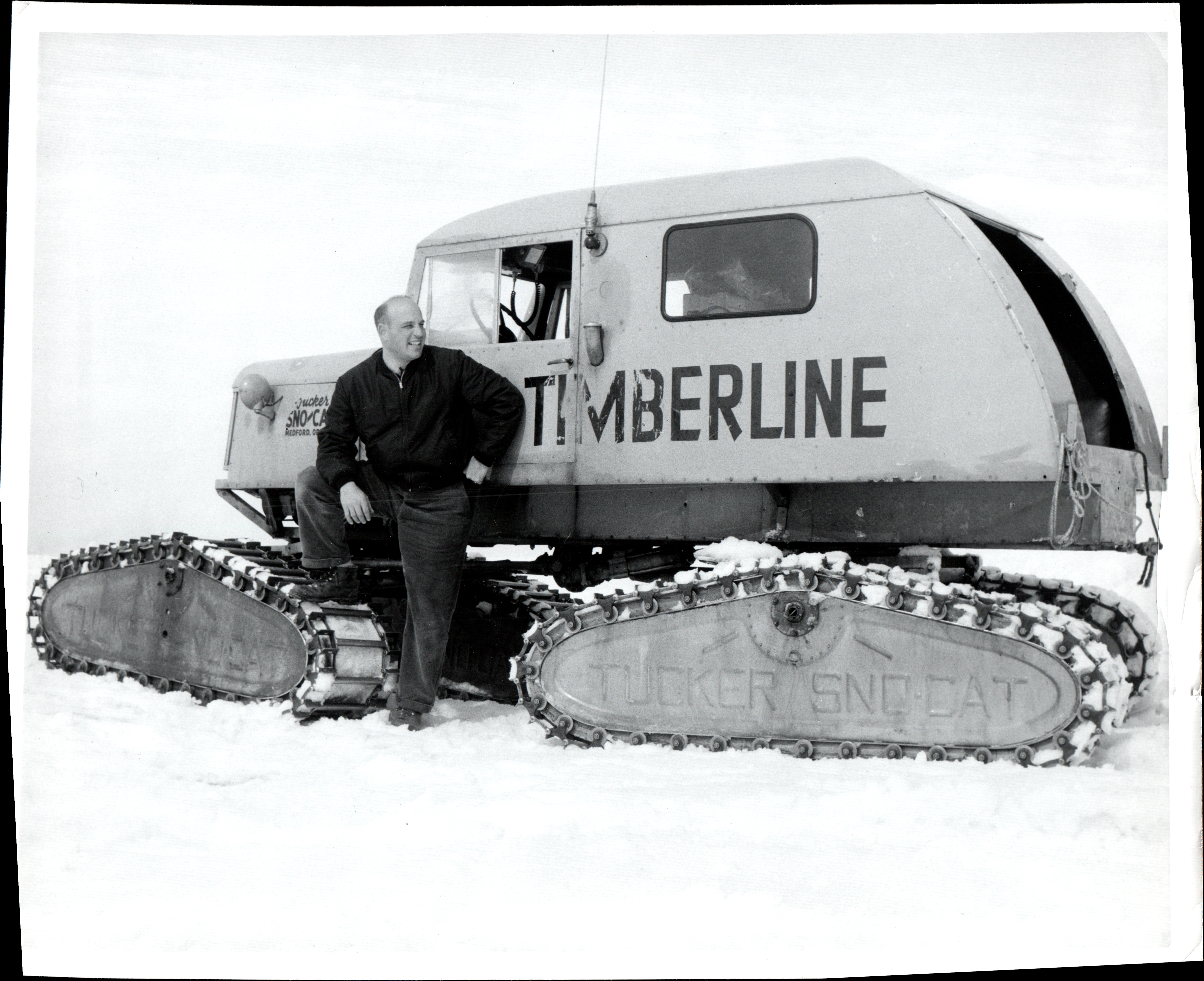

Once Kohnstamm got the lodge back up and running, he then focused his energy on the lifts. A huge part of his legacy is pioneering the nation’s summer ski scene. He hired Austrian skier Pepi Gabl to run the ski school and during that very first summer in 1956, Gabl offered the very first summer ski camp on Hood—The International Summer Racing School. There were three ten-day sessions for invited ski racers. Campers rode up the Magic Mile lift and then hitched a ride in Tucker Sno-Cats to access the Palmer snowfield. Much like today, they practiced skiing and running gates on the Palmer snowfield all morning, then skied down through slushy snow to the lodge in the afternoon.

Under Kohnstamm, summer camps continued to grow. He saw his vision of a lift to the top of the snowfield realized with the installation of the Palmer Lift in 1979 (the lift was replaced with the new quad in 1996). The ride down from the top of Palmer to the base of the Magic Mile clocks in at a two-and-a-half-mile run—leading to where the summer scene goes down.

It was almost all ski racing on the snowfield up until the ‘80s… then the snowboarders came. Beyond seeing the limitless possibilities of summer skiing, Kohnstamm also saw the potential of snowboarding and embraced it from the start, with the earliest snowboarders sliding turns in the winter of 1982/83. A deserved nod goes out to Kohnstamm’s wife, Molly, who took up snowboarding and also advocated for the sport in those early days. John Ingersoll, co-founder of High Cascade Snowboard Camp, recounted his meeting with Kohnstamm one day in the early ‘90s. Ingersoll said, “R.L. stopped me and he looked me in the eye. He said snowboarding was going to be really big. ‘You’ve really got something here, John,’ he told me.”

The Legacy of Summer Snowboarding

The Palmer snowfield has been ground zero for the progression of snowboarding, and that’s largely due to Timberline’s dedication to progressing freestyle terrain at a time when other resorts were still actively banning jumping, and in some cases, snowboarding altogether. In 1992, Richard Kohnstamm’s son Jeff, who grew up in the lodge, took over from his dad as the President and operator, carrying on his father’s legacy to this day. Kohnstamm brought on staff who cared about the sport and freestyle progression, including longtime General Manager, Steve Kruse, who oversaw operations from 1993 to 2020. Kruse is credited with founding Cutter’s Camp, bringing together terrain park groomers from across the country to dial in their techniques, along with pioneer park builder Jeff Flood. Flood was a Timberline groomer who is widely respected as one of the original innovators of man-made freestyle terrain features, responsible for builds at Winter X Games from 1999 on. Chris Gunnarson, founder of Snowpark Technologies credits Flood with being a mentor to himself and Frank Wells, two builders who are themselves considered legendary. Flood tragically passed away in a car accident in 2006, but not before leaving his mark on the progression of freestyle terrain.

As president, Jeff Kohnstamm, like his dad, never second guessed his commitment to enabling snowboarding. When asked about whether there was ever conflict or hesitation related to snowboarding, he shrugged off the suggestion. He shared that the vibe was different in the Northwest than other parts of the country back then. “It was a little grunge, a little anti-establishment in the Northwest—so snowboarding wasn’t as counterculture as it was everywhere else,” says Kohnstamm. He points to the Howatt family at Mt. Baker as contemporaries who also didn’t blink at welcoming and promoting snowboarding. Kohnstamm also saw the summertime as a huge opportunity to fine-tune the snowboarding experience at Timberline; noting that snowboarders were the first to use the deep veins of snow below the groomed lanes for the parks and halfpipes. Timberline also had the staff to get the job done and benefited from coordinating through the camps. “We had operators in snowcats who were familiar with it and knew what the kids liked, and because of the way we operate in the summertime we were catering to a group of kids doing a singular thing under a coach’s supervision through these camps,” says Kohnstamm, “it allowed us to be a little freer over the years and to refine those park areas, as opposed to if we were trying to operate a resort and meet the needs of all the resort users.”

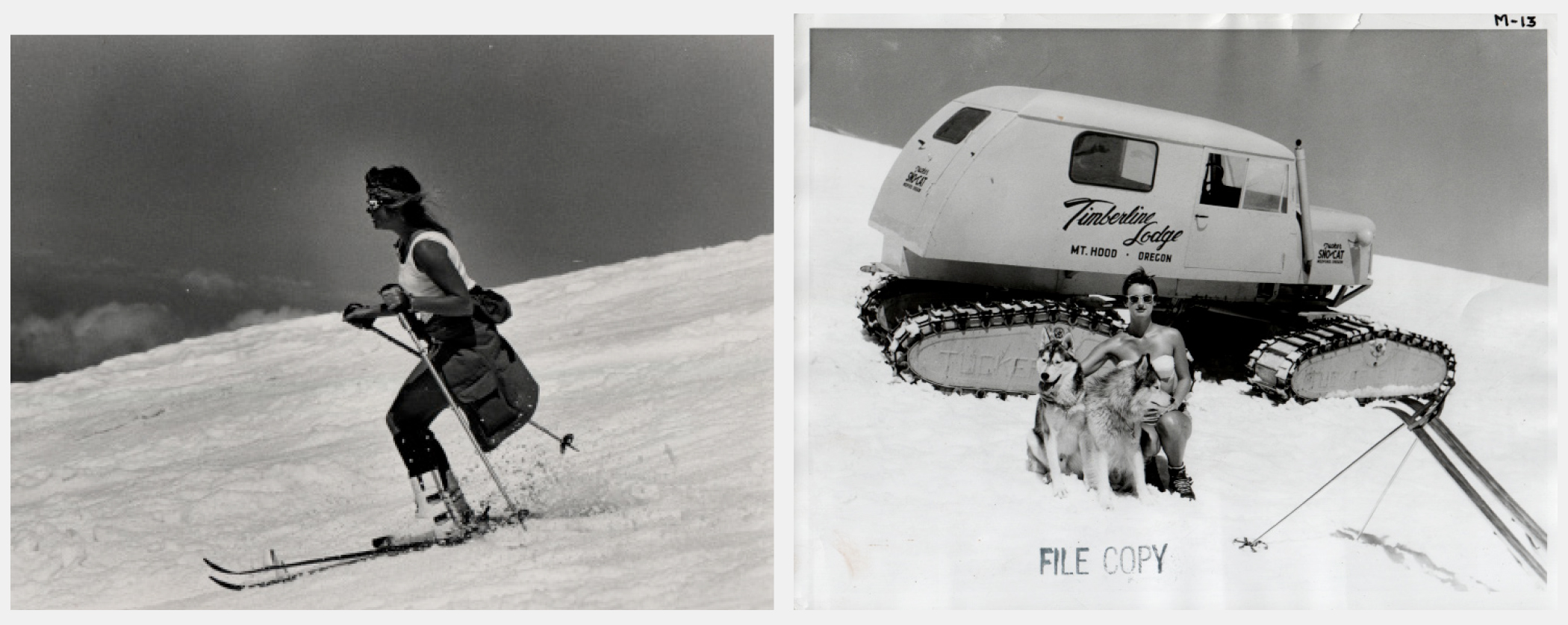

As the features progressed, so did the riders. By 1999, snowboarding accounted for 60 percent of summertime ticket sales on the snowfield with four main snowboard camps: High Cascade Snowboard Camp, Windells, Mount Hood Snowboard Camp and the U.S Snowboard Training Center all operating their own on-hill terrain parks and facilities with dedicated builders and diggers. Professional snowboarders descended on Hood, riding at the camps as visiting pros and coaches, or just dropping in for after-hours shoots. Some of the most legendary moments in snowboard history have gone down on these slopes, all of it documented by the now-famous film crews and photographers, from Whitey, Mack Dawg, and Robot Food to Bud Fawcett, Trevor Graves, and Andy Wright.

The peak snowboard moments stretch back decades now, too many to list, so many tied to the moment in time. Maybe Morgan Lafonte backflipping in her bra stands out to you as it did to me as an impressionable young camper in the early ‘90s. Maybe it was Terje and Daniel Franck, fresh from Norway destroying every feature in sight with the most insane style. Maybe you were there for a rare Jamie Lynn sighting. There were the summers of little Shaun White hiking the pipe endlessly. JP Walker and Mikey Leblanc airing over the pipe. Peter Line and Joey McGuire sending it deep. And that’s admittedly, just the early days. Hood is where fashion trends take off like wildfire, Cobra Dogs get housed, epic skate sessions go down and, maybe less now than at one time, legendary end-of-session debauchery goes off in Govy. The on-snow experience is unlike anywhere else, from the big productions of Burton Abominable Snow Jam to the Rat Race, the days of banners and branding everywhere, to the features alone. All of it.

I never knew it back then, across the decades of traveling to Hood—as a camper, HCSC staff, TWS media, a Rat Race competitor—but now I do, we have the vision of the Kohnstamm family to thank for these days on the snowfield. Richard Kohnstamm passed away in 2006, at 80 years old, in his beloved Mt. Hood cabin. His son Jeff Kohnstamm is still at the helm, the resort is now nearly 70 years into family management. The elder Kohnstamm was there to see the first halfpipe built on Mt. Hood. On observing the snowboarders hiking up the pipe, he happily reminisced of the 1950s, when alpine skiers hiked for runs after the lifts closed. It’s easy to imagine a scenario where snowboarding and freestyle riding weren’t embraced at Timberline. Instead, snowboarding was actively fostered and supported, cultivating its progression. Next time you’re up at Hood enjoying the glory that is summer snowboarding, take a moment to consider the past, because there’s a scenario where none of this could have come to be. Thankfully, it did.

Summer Snowboard Camps at Timberline: A Brief, Incomplete & Possibly Flawed Timeline

In 1988, John Hartung, owner of Rebel Skates skateshop in Portland, launched the first and only Rebel Snowboard Camp with pro riders Mike Estes and Kris “Jaymo” Jameson. The next year, Gnu Snowboard Farm started in its wake. It was staffed by Gnu team riders with the “lightly-supervised” campers posted up at Park Place in Govy. The camp had neither a dedicated lane or a halfpipe in that first year. Locals were hired to help dig the pipe, including Kurt Heine, who went on to develop Heine Pipe Tools, and a coaching staff that included Tina Basich, Jeff Davis and Jaymo. As Karol tells it, “Mt. Hood became a focal point of snowboarding that summer. Pro riders, media types, freeriders, skaters and crew all began descending on the once quiet ski-racer town of Government Camp. With no rules, street-level entertainment was at an all-time high.” Gnu teamrider Chris Karol continued the camp as the Karol Snowboarding Camp for another year.

Once the ball got rolling with summer snowboard camps at Hood, the floodgates opened. High Cascade, Windells, USSTC and Mt. Hood Snowboard Camp to name a few launched out of the gate, with HCSC and Windells making the biggest marks over the years.

In 1990, the inaugural year of High Cascade Snowboard Camp, the glacier saw 300-plus campers over five ten-day sessions. The snowboarders took control of the coveted “lane one” allowing campers prime real estate for slalom training, freeriding, and access to the vein of snow below the race lanes where the halfpipe lived. “It was a takeover in every way,” says John Calkins, co-founder of High Cascade Snowboard Camp along with John Ingersoll, referring to the almost immediate and overwhelming presence of snowboarders on Palmer. That first summer featured a slalom course and a hand-dug halfpipe courtesy of “the diggers.”

Windells Snowboard Camp initially launched in Whistler, where, in 1988, the Sims/Summer Shred Session put on by then Sims team riders Craig Kelly and Tim Windell went down, which went on to become the legendary Craig Kelly Shred the World Camp. “Whistler was amazing,” says Windell, “I wanted to move there. Yet rallying the coaches on a Saturday and Sunday morning was near impossible.” Shred the World camps gave way to Windells Snowboard Camp when he moved the camp to Timberline in 1991. Tim points out that there were no training grounds outside of the competition itself back in the day. He says, “Back then, you’d show up to a World Cup event and you’d get to ride the pipe the day before; that’s it. The whole premise of camp for me was, ‘I’m going to start a camp and further develop out the sport.’”

The camps grew and grew and grew along with snowboarding. As Windell tells it, the 2008 recession didn’t actually affect the camps, but things started to slow down in 2011. This was the beginning of the mergers that led to High Cascade eventually folding into Windells and becoming a single super camp known as We Are Camp on the super campus in Sandy. Likewise, the on-hill facilities merged into Timberline’s Freestyle Training Center—which today includes a 22-foot Superpipe with a halfpipe spine airbag, progressive jump and transition features, rail and jib features of all shapes and sizes all sessionable via multiple handle tows, plus a boardercross course, all amounting to the single largest summer terrain park in Timberline history.

We Are Camp includes Seek Skateboarding, MilePost ThirtyFive Mountain Biking, High Cascade Snowboarding, Windells Freeskiing, and the Wy’East Academy. In 2019, We Are Camp celebrated the 30th anniversary of snowboard camps on Mt. Hood. The head of the whole shebang, Kevin English, invited past employees to come to the campus to celebrate all the history the best way he knew how—to camp, snowboard, skate and celebrate together as a community.