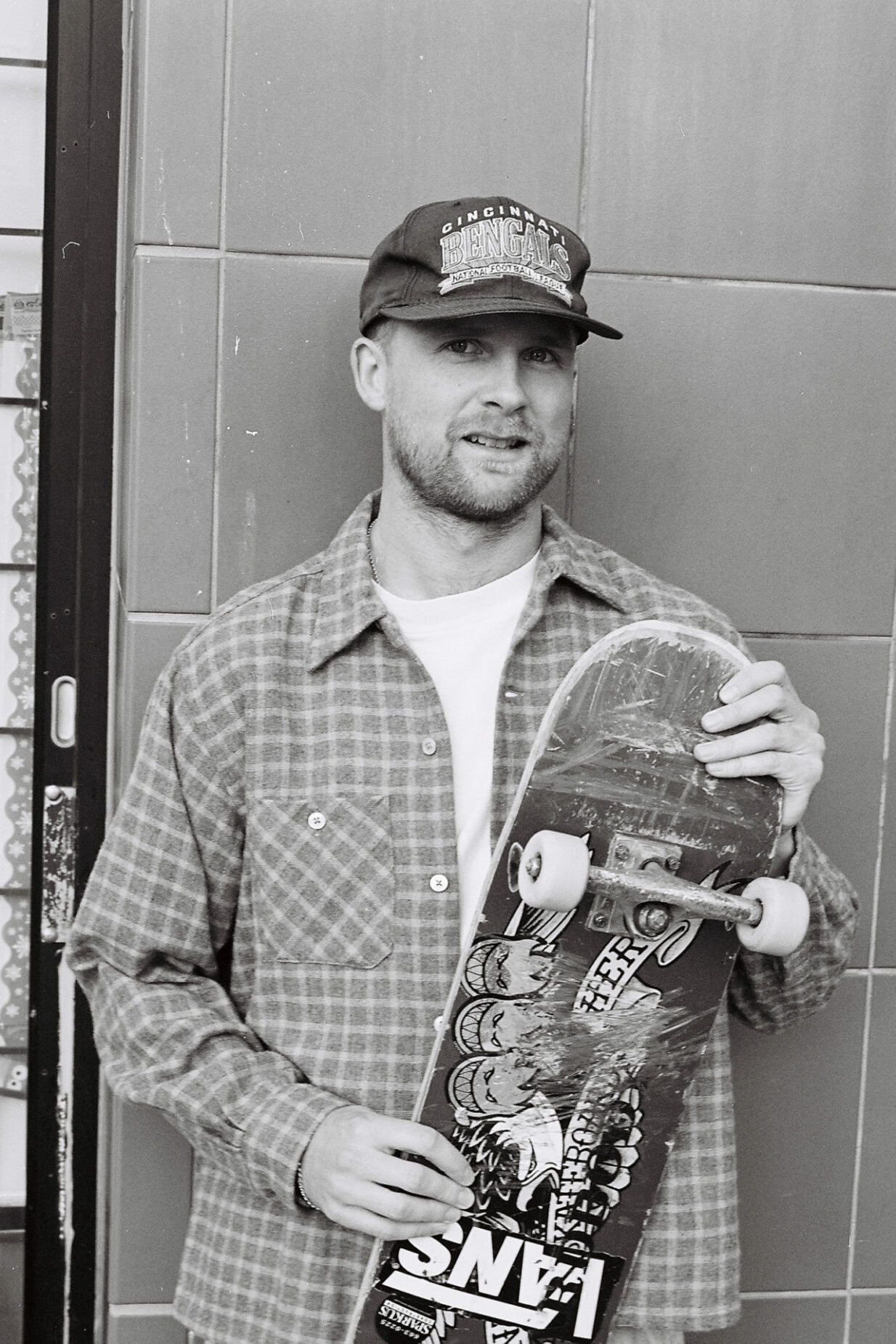

Introduction by Ian Boll; Interview by Jon Stark

A guy like Jake should need no introduction. But this time is different. The name Jake Kuzyk now carries a new weight, something that makes me smile. For the first time, we get to meet the Jake who’s comfortable telling the world he is gay. And not just that he’s gay, but that he’s never been better because of it. That’s the part that should make you smile too. Jake has chosen to share with the world his most tightly kept secret. And that’s a terrifying thing—I don’t care what it is you’re hiding.

Timing is everything. Jake has wanted to speak up for a while, but just as anyone’s confidence wavers when confronted with a towering decision, Jake questioned how to do so, and in a meaningful way. When Tanner came out, he called his friends and family and unknowingly planted a seed with Jake that would lead him to make the most important admission of his life. It demonstrates the impact one instance of courage can have, in that moment toppling the archetypal idea of what a snowboarder should be. A wave of change has now been set unstoppably in motion to make our community open to all.

Jake’s story, like four others—Kennedi, Chad, Jill, and Tanner—closely shadow many more. The Monomyth, an idea developed by Joseph Campbell, is a synthesis of countless stories written throughout history with a universal theme. Grossly abbreviated, it breaks down like this: A protagonist is faced with a challenge and after first refusing, they are helped by a mentor to cross a threshold. They embark on a road of tribulation, usually assisted by allies, until facing their greatest trial yet. Upon completion they return with knowledge to use for a greater good. Jake’s journey is the epitome of these heroic stories. Through his deep introspection and articulation, this interview can ultimately act as a guide for many—and not just for closeted snowboarders, but for any individual afraid of change.

Jon: So why are we talking today?

Jake: Well, we’re talking because it's Pride, and some of us are sharing our stories. I'm gay, and I'm talking about it.

The first time beyond maybe your inner circle of friends?

Yeah, I told a small group of family and friends over the last year or two. But for the public, and from a career perspective, this is the first time I'm talking about it.

Which came first, skateboarding and snowboarding, or knowing you were gay?

I mean, I've known I was gay forever, but when you're really young, you don't really know in the full sense. You understand that something's different, but it's tough to comprehend. I’ve been doing both those things every day since I was 10 years old. It wasn't until years after starting to skate and snowboard that I fully realized this part of me was different.

Are you currently in a relationship?

Honestly, that's a tough question to answer. I think so. Maybe? I have been seeing someone for a while now, and they're really great. We live in the same neighbourhood. They like to snowboard, and they’re into a bunch of creative things. We have a lot in common. He’s the best! But are we in a relationship? I don't know if I can answer that. Uh oh.

Do you think this would have come out sooner if there was another professional snowboarder who was openly gay and male?

It definitely would have set things in motion. It seemed so difficult to be openly gay and have this career, these friends, and all the interests that came along with that. I felt like if I started to show this part of myself—that becomes really scary because you just don't know what's gonna happen. When you're alone thinking about this shit all the time, you develop really wild ideas of what it might look like and what could happen. My career has always moved in this positive forward direction. So I was afraid to risk damaging that. I didn't want to sacrifice what I already had. That's really foolish because I know now that obviously isn't the case, and there is no sacrifice. It's just better. Everything is just so much better. I feel much closer now to the people in my life, and I haven't lost any friends along the way.

There isn’t a how-to guide to coming out is there?

No, none. We all have interests, and so you shape your world around them and you love it. It's what drives you. So you go all in. That's who you are, and it’s not a lie. That's the real deal. Then this other part of yourself can feel so conflicted with the rest of your identity, especially at a young age, but it really doesn't have to be. I wished I would have realized that sooner, and yeah, seeing someone else who looked like me, did the things I love to do, I would have taken a lot of comfort in that and been willing to move forward sooner, dating guys and just not being so afraid. For a long time, I just didn't want to stand out in that way—being gay, different from everyone else. A part of me knew it would bring happiness, but there was no path. I hadn't seen anything like it.

Yeah, just the fear of uncertainty.

Which is just ridiculous, dude, because now I'm 30 and have been dating for some years. When I think back, I cannot believe I felt that way. It’s distant. I’m so much happier now.

It's like being a part of the queer community for the last couple of years put things in perspective in hindsight, like you said.

I've realised some things. I can just be me. I'm definitely different than some people in the queer community that I hang out with, but that's not a big deal. That's the best part about it is we're all different, and we're all still friends, and it's cool. You can be a big time snowboard nerd, and you can be gay. It doesn’t have to be one or the other. That's something I never understood. I thought there was a line somewhere–this imaginary line.

Ian: Who's been your support system throughout this process to come out?

Tanner Pendleton, without a doubt. I had no idea he was gay, so when he told me and I put down the phone, I cried in my room. I couldn't believe it. I've known him for eight years. We live really similar lives and have such common interests. That really just blew the doors off for me. When I hung up the phone, I knew then that was it. Something shifted, and there was room for me. Tanner had broken this mold that held me back.

What were your thoughts during the time between Tanner telling you he was gay and when you eventually told Tanner yourself? How did that conversation go?

When Tanner told me he was gay, I felt completely disarmed. I knew we would see each other in Montreal for Dillon’s memorial and that I needed to say something. It was late that night, and we were with a huge group of all his friends in the park. People from all over. It was really beautiful. Tanner and I had a short moment alone. I knew he was leaving early the next morning and that was my only chance. I just said it. “I’m gay.” I broke down. We moved to an empty part of the park and talked for hours. We could relate on so many levels right away. It was this huge release.

Was there any notion during the filming of your Vans welcome clip or Landline that Tanner was an ally?

No. Well... I shouldn't say that. Tanner was often quite expressive about supporting the queer community in ways that I thought were really cool when I was closeted. I would hear him state his opinion strongly and not stand for people saying harmful shit. I noticed that and always respected him for it.

Cole Navin: All of this must have been a huge relief. What are you looking forward to most now that this is off your chest?

Selfishly, I'll say what I'm looking forward to the most out of all this is not having to look over my shoulder, watch my words or wonder where I'm going to go on a date, who we might bump into. Always wondering if people are going to talk about sex or relationships and how I'm going to respond. That shit is so exhausting, and I'm so hyped to not do that anymore.

Jon: In Tanner's interview, you asked if he felt like he needed to bury himself in his work to prove his self worth. Do you yourself relate to that as well?

I wanted to do the best job I could, and I wanted people to appreciate me for the work. That was it. I didn't want them to know anything else because I didn't have the answers myself. I was having fun when I was snowboarding, and I was having fun when I was filming. Having these projects with constant stimulation I could be more satisfied at the end of the day—even knowing I'm in the closet—because I'm producing things that get a positive response. It allowed me to feel some sort of validation towards my identity. That's strange to admit, but I also think it's very natural. We all crave that acceptance.

Without time alone, personal time, it's really hard to work on yourself.

I mean, I tried to ignore it. Just moving through life, distracting myself with things I loved and then going to bed. Then when you're about to fall asleep, that's when it sucks.

Were you concerned this could have a negative implication on your career as a professional snowboarder?

Pretty much everyday. I was most concerned about spending time with people that knew me for years as one way, and I feared they wouldn't accept me as gay. How will I be able to communicate with them, will they welcome me, and are they going to freak out if they have to be alone with me? Thinking I would lose opportunities to travel and maybe even my career was freaky. I was trying to balance what was more important. It's like you're a little kid. I love snowboarding; I love skateboarding. That's what I want to do. But you also need connections; you need people; you need love.

You're part of both the skate and snowboard communities, and especially after that Vans Loveletters piece came out last week, it just feels as if skateboarding's years ahead of snowboarding when it comes to accepting the queer communitity.

Before Brian Anderson there was very little queer representation within skateboarding. I think that moment really helped people to understand and to see that those differences were okay. Before, there was such a narrow idea of what a person in skateboarding needed to look and be like. Now there's just so much diversity, and the acceptance is widening because it's cool. It's cool to be totally fucking different than somebody else. No one wants to see the same person over and over. Where before, it seemed like there was this script to follow. Even in our own snowboard world there was a path to success with sponsors and videos, and you didn't want to stray too far from that because then the opportunities might fail. So you stayed on track to try and satisfy company needs and the people around you. Now it's a lot different. People are doing way more of whatever the fuck they want, and it looks good, and it doesn't have to be one way.

Why hasn't this topic been broached yet in snowboarding?

2020 seems to be the time when at least five of us now have come together to talk about it. But you know there's been gay people, queer people in snowboarding since it started. Being gay isn't some new thing. We just talk about it now. Personally, I'd love to know who they were and what their lives were like, and I hope that they're happy. I don't know, man. It's a trippy thought, but it's real.

Just statistically speaking, there have always been gay people in our community.

Exactly. Maybe some felt they had to give up on fulfilling a queer life because there's a lot of that too, still. People can't find self acceptance and that fucking sucks. How is that possible? It goes back to what I was saying. I dealt with that for many years. I wasn't self accepting. I had so much internalized homophobia. It was never projected outwardly—I never hated other gay people—I just didn't feel like that was me, so I couldn't relate. I beat myself up for it. I'm so grateful to have found people like Tanner, and then through that, others like Kennedi, who have helped me to understand this piece of myself and communicate in this new way. What if I never found that? I could have been one of these people who stays in the closet forever. Never accepting it just staying unhappy. That's horrible.

Ian: It’s scary to think about all the people who have felt unable to come out due to the fact that our industry has been so historically unwelcoming to the queer community. Did that have a big effect on your own timeline? Did you want to speak up earlier?

I've wanted to talk about this for a year now. I wanted it to be something that could benefit others, and I didn't want it to feel like marketing. But I couldn't really solve what that looked like. I was also really afraid. Everyday there is so much new stuff for me to learn about the queer community; this is still a new world for me. So to step out and tell everyone my story like I have all the answers is scary—I don't have the answers. I don't know anything, but I'm trying. And so it really took having this group, the five of us, to all be able to say something together. This makes sense for our world. The people who love snowboarding can come here, see these interviews and hopefully learn, whether they’re gay or straight. So I don't know if I could have done this when I was 16, even if I wanted to. Or 22. I just don't know. I can't say for sure, because this is how I am, and this is who I am, and this is what's happened.

Jon: How did your upbringing affect your perspective on your own sexuality?

I was raised Catholic. We went to church every Sunday. So it was just a lot of environmental influence flooding my mind, and thinking that I couldn't be gay, or not even that I couldn't. It was just, "I'm not gay." Trying to solve the mystery of your past is a bit gnarly.

Yeah, being so affiliated with a religion, you're feeling one way, and learning another thing. That's a difficult knot.

I grew up in the prairies with two older brothers. All our family friends were straight, white, perfect homes, all with kids, and happy marriages. That lack of diversity can make your world seem very small. Therefore, my own homosexuality didn’t fit. That's not to say my parents did a bad job. They were the absolute best; they did everything they could for us. And they nailed it. To this day, so supportive. I told my Dad that I was gay two months before he passed away, and I never felt closer to him before in my life. In those two months, we saw each other a lot. He came here to Vancouver. I had just bought an apartment, and we did some renovations, He could see me for real, for the first time, parental guidance had sort of finally fallen away. And we were just friends.

That's really special. I didn't know the timeline of you coming out with your dad passing away. It's tragic that you lost your dad, but really special that you got to share this last piece of information with him.

It gives me peace.

You lost somebody else just before that too. Dillon’s passing was a huge blow to our friend group and the snowboard community as a whole. How did his death affect you in regards to your journey to self-acceptance and eventually coming out?

When Dillon died so much was going on. I think for everyone, we were all just trying to understand what that meant. I couldn't stop thinking about the kind of person he was. He held nothing back, ever, and he was so kind to people, so accepting. He knew how to have fun, and he knew what he loved. He loved his friends. I noticed and always admired that. Once he passed, I realized for myself, "It's like he's telling me I need to make changes." Because what is the point of moving forward and still living this way? I'm protecting others more than I'm doing anything for myself. That was the cool thing about Dillon. He knew what he loved, and he wasn't going to change that for other people. That was the biggest thing I learned from him. The day he passed away I knew. I’m gay. I'm telling people.

I always referenced that last interview he did where he was talking about creating a space for different races, genders and sexualities to come together to party and listen to his music, and have the entire experience be about acceptance.

I saw that, man, and I just melted. I couldn't believe what I was reading. He was speaking to everyone. But it felt like he was talking directly to me, because that was crazy. To then see him put it in print like that, I was just tripping.

Was the suppression affecting your relationships?

I put up this front of strength, or I don't know what it was. The constant self preservation is exhausting, and you don't even understand the ways you're doing it until you stop and reflect. Faking heteronormative behaviours, watching your words, hiding from conversation. Before, when I would leave the house, it felt like I was just treading water for 12 hours. And then I would get back in the door, and just take a huge breath. You can't really connect with people when you're not being honest to yourself.

I can imagine those emotions compound pretty quickly.

You try to be strong. You try to use these things to move forward, but at the same time the realization of them can hurt your ego too. It's scary to tell everyone you're a 30-year-old gay man for the first time, because they think you're weak, or they think that you don't know yourself, or that something's wrong with you. Some things you can't explain. Eventually you have to let go.

This time period must have been so emotionally draining for you, but it seems like you made it to a much better place?

A lot was going on. But dude, my life is pretty crazy. I’m a professional snowboarder; I have an apartment; I get to travel. There is so much social injustice and hardship I do not experience as a CIS white male. I’m very privileged.

Cole: To someone who is upset or confused reading this, what would you say to them—to the people who might not understand the significance of you choosing to tell your story?

Ask yourself what the problem is—what effect does this have on you personally? Why would you take a negative stance and for what reason? There is no point in trying to discredit someone else's story, because you don't know shit about it, and the only thing you can do is try to learn. And once you do, you just have to accept them, because their struggle is valid. And you don’t have to experience that. You have to re-adjust and rewire to realize, "Yes, we are different, but this is okay." Maybe you don't hate that person who looks different than you, but you don't necessarily accept them either, and you don't make space for them. You just keep living your life, promoting your ideals and your understanding of the world. And then these people just have to suffer in silence, because nothing has been created for them. The least you can do is just make a little room, because it's not going to take anything away from you, it won't.

But hopefully this is the beginning, you know?

Every time I hear a new story from a queer person, especially with similar interests, it is so inspiring. You go from feeling uncertain and alone to thinking, "I'm gay, and this is fucking sick." The more you say that, and the more you celebrate it for your own community, the better you feel, and you don't care what other people think. Because the hardest part is trying not to care what other people think.

Ian: For someone who's currently in the position you were facing, especially with the stigma around being a gay athlete, what advice do you have for them navigating it?

It can be very difficult, but try to see the queer world around you. Don’t push it away even if it feels foreign to your identity, allow it space in your life, and allow it to come in slowly—whether that's researching online, hearing people's stories or making new friends. Trying to find some comfort is what's going to shift things for you internally. Hopefully you can relate in some small ways, because the wall will fall so much lower every time you do. I was afraid to look outward and hear those stories. I was scared the more I learned about about gay culture, the more it would want to explode out of me and I didnt feel ready for that.

It seems like we can’t stress enough how helpful it is to have someone to talk openly about this?

Once I had Tanner to connect with, it just changed everything rapidly. In a month, I felt like a different person living a different life. We talked on the phone nearly every day for over six months. He'd call me or I'd call him, and we would just bounce things back and forth. Trying to navigate all these new thoughts and feelings. We were really honest with each other. When you're holding that inside, it just needs to come out. Everything felt like it was in fast forward. So maybe what I'll say too, is try to find those allies who can support that journey and support that exploration of finding how you feel.

Jon: Yeah. Tanner was a real big piece of this puzzle in the story today.

Yeah. He's the biggest piece, whether he likes to admit that or not. He's like Mr. Humble, but he's a huge part of this whole thing.

You thought your voice was alone, but now look at the reality of power in numbers.

Completely. It's so cool! It gives me so much confidence knowing that we're all doing it together because I don't think I could have done this alone. So thankful for all these people, and I'm thankful for you guys. I haven’t slept in four days just thinking about doing this.

Agreed. The feeling is mutual. It's just like the civil unrest is all of a sudden challenging me. First and foremost, I'm 34 years old, and it's like, "When are you going to decide to grow up?" A part of snowboarding is this Peter Pan effect. Chalk this one up as one of the many reasons why this hasn't been addressed yet.

The selfish aspect of it is perpetuated. It's rewarded throughout our careers, and it's really hard to understand and get away from, because it's a part of what you do. It's how you are valuable to the companies you work for.

Yeah. It's a strange relationship and taken out of context sometimes.

We have all made these mistakes, judged people. And maybe even acted on it. I've said homophobic things in my younger life. I'm not claiming to be free of that either. I’m not proud of that, but you can change. History doesn't necessarily make you a bad person; it's just that now you are learning the effect your actions can have. Some of us have the privilege to ignore these problems that society forces upon marginalized groups—to not see—because we are not always affected. Whether that's sexuality, race, or whatever it may be. It's so easy to just keep going and to not think about others, but now, some are starting to realize we need to learn and unlearn, and that's important. That's what's going to change things for everybody.

Anything else you want to say?

To anyone who does read this interview and is questioning or feeling afraid—I don't care who—you can reach out to me, online or in person. I want people to know they can ask me a question or two, or three, or four, or whatever, and I'll do my best to try and help. So if there is anything they want to ask or say, I’m down :)