“Is snowboarding an art or a sport?” is a question so over-asked it’s lost any sense of edge or intrigue. It’s both of course, or pure art for some, pure sport for others, like most “action” sports actually. One could even argue that all sports, however regimented, contain an element of art, and all art, however abstract, contains a bit of sport — with its inherent competitiveness and focus on virtuosity.

A more compelling question for me has always been: “Is snowboard photography Art?” And I do mean to capitalize here; art v. Art, as in: “In conversation with the history of and current practice of installation art/ fine art photography/museum exhibitions/gallery shows/etc.” I try to imbue my own snowboard work with as much attention to color, composition, and “meaning” as I can, and I certainly feel and think a lot when I encounter really well-made snow/skate/surf work. While I don’t have a solid answer, I’ve been considering this question more deeply recently.

Over the past few years, a number of brands and media practitioners in the outdoor and snow space have been explicitly mirroring production techniques and display methodologies typically found in the art world. Their reference points are more Artforum and Contemporary Art Daily than Thrasher or Red Bull Illume.

Maybe I’m too siloed in snowboard culture, but I follow skating and surfing pretty closely, and I haven’t seen this exact trend in those spaces (do let me know if I’m missing reference points here). Yes, there is a lot of overlap (much more so than in snowboarding/skiing actually) between skating, surfing, and the art world; Mark Gonzales’ performance-art skating, Ed Templeton’s career as a respected photographer and multi-disciplinary artist, Gagosian-represented artist Alex Israel’s surf inspired exhibitions, recent Gagosian addition Tyler Mitchell’s skate-related origins… I could go on.

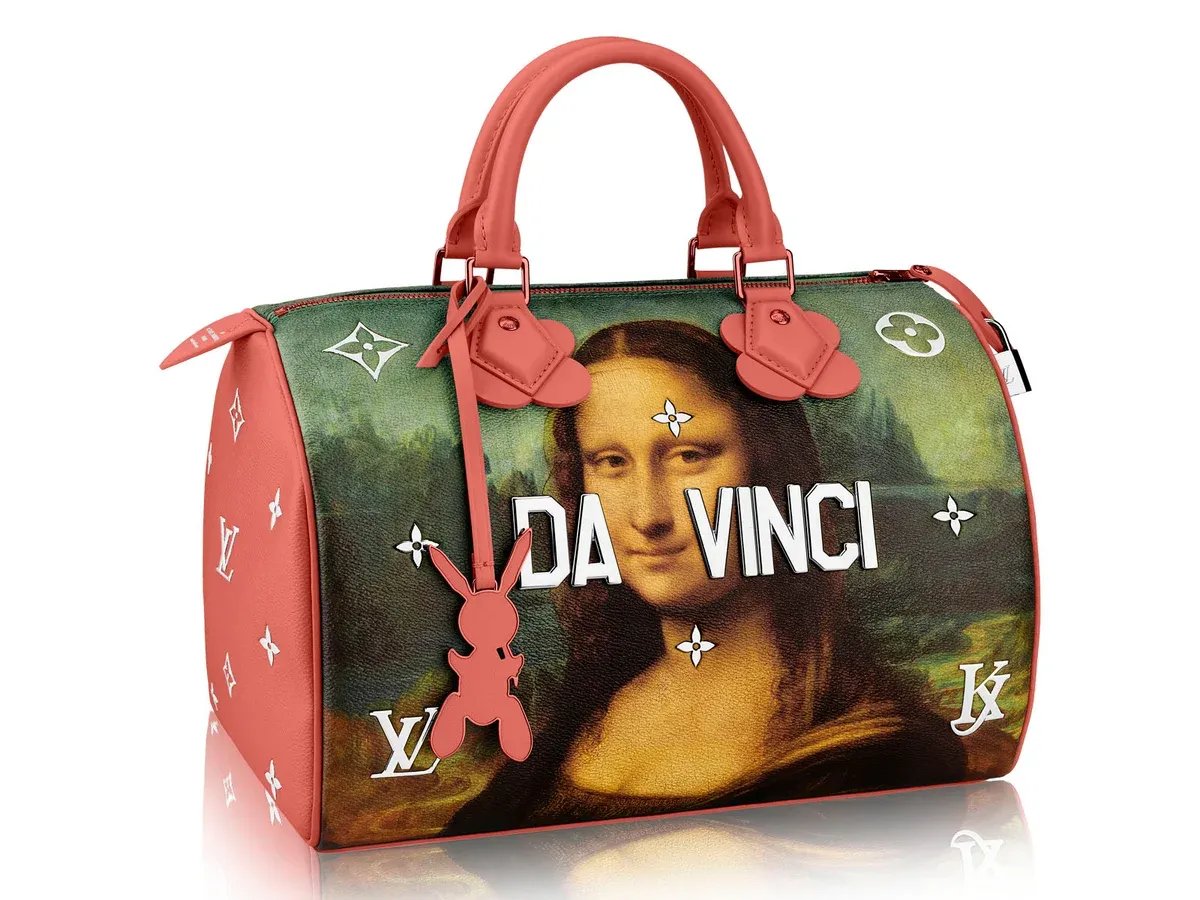

And yes, there are collabs between surf/skate/snow brands with A-list contemporary artists. See Hayden Shapes collaboration with the artist Daniel Arsham and their resultant “Eroded Surfboard” sculpture and associated products. There’s also Supreme’s 2025 Damien Hirst collaboration (not their first with this artist). And in 2016, the artist Jeff Koons released a collab board with Burton. This sort of thing is related to what I’m seeing but it’s not exactly what I’m seeing. There is still a separation here, Damien Hirst isn’t photographing the cover of Thrasher, and Daniel Arsham isn’t filming the latest Craig Anderson edit.

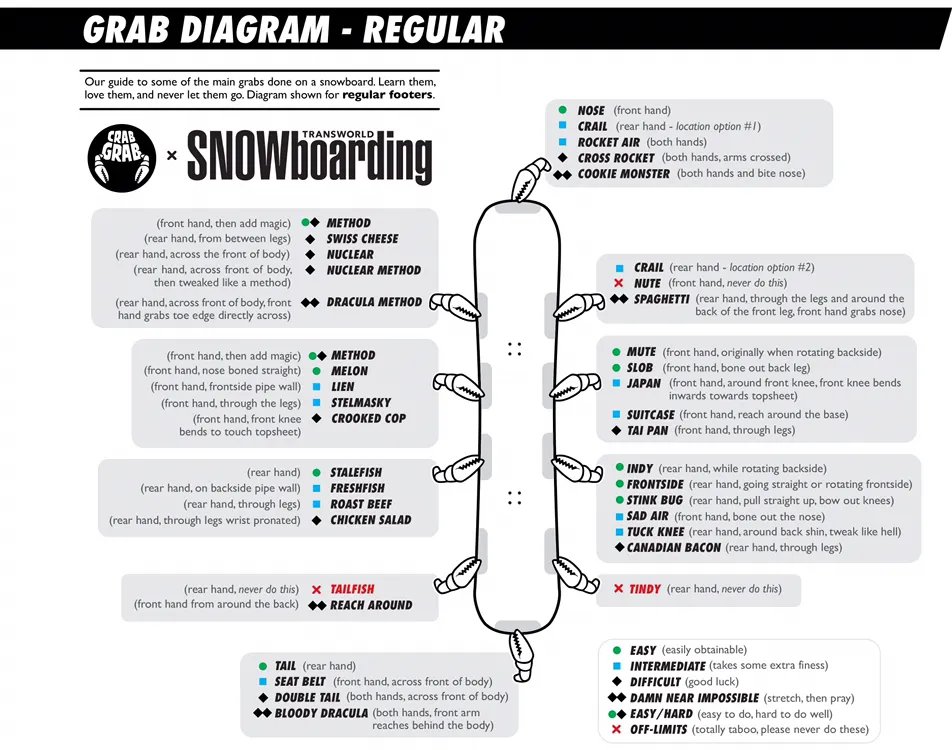

The first time I noticed this aesthetic overlap/leaning was in Christian Haller and Kris Ludi’s SOFT and GLUE films. These films were, to my eye, extremely sophisticated, and taking their inspirations from outside of endemic snowboard video history. For example, SOFT features a single slow-motion shot of a Method grab that lasts almost a full 2 minutes. Andy Warhol’s “Empire”, the 1965 8-hour film of the Empire State Building comes to mind, or more recently, James Nares’ 2011 slow motion study of NYC, “STREET”.

Not coincidentally, Kris Ludi went on to found the Swiss production company Hillton, who made this year’s Arc’teryx film “Every Island Has a Name”, which premiered with a full-on exhibition including photography, performance, and sculpture. Arc’teryx states that the film “is a celebration of snowboarding as an art form—that is, to prioritize process over output, and form over function.”

Hillton was also responsible for the experimental 2021 film “Chroma”, which deftly straddled this art/sport line. In association with “Chroma,” photographer Silvano Zeiter produced these interactive photography sequence sculptures. These “Polyscopes” depict a few second snippet of photographic/filmic action as a physical object, able to be “replayed” via viewer interaction with the device.

To my eye, these are art objects, but made for an already “read-in” member of the snowboard community. They use all the tactics and production techniques of contemporary art, both physically and conceptually, but they reference snowboard culture and snowboard history specifically. Your average non-boarding person could absolutely appreciate them, but they will never “get-it” the way someone familiar with snowboard media history and culture might. They still maintain, as one of their goals, the depiction of “good snowboarding”, as well as a relation to the film from whence they came.

I was able to pin down Silvano Zeiter on some of this stuff and here’s a couple snippets of what he had to say:

“I think this question can’t be answered universally, but to get closer to the bottom of it, one might first ask what art is in general—and that perception is highly individual. Also, is snowboarding itself art? If you look at art as a medium through which you can freely express yourself, your emotions, your feelings, and potentially try to translate this to others by displaying it, then I’d say it definitely is.

He goes on, in reference to “Poly”:

“To me, the most intriguing photos from the project are the ones that are so abstract you can barely tell what’s going on. A snowboarder in the air could suddenly resemble a flower. I guess those were the shots that didn’t really resonate much within the snowboard world, but they might come closest to what some people consider art.”

And finally:

“I can’t tell you whether this is art or not and I think everybody has to decide for themselves. But what I do know is that anyone who creates something real and personal, exposing their vulnerability and stripping down emotionally in the process just to express something they believe in, has my deepest and most sincere respect. Maybe that’s all art really is.”

A healthy and insightful POV from one of the photographers at the forefront of this “movement”, and in my opinion, one of the best to ever do it in the snowboard space.

There are a myriad of recent examples of work in this vein. Cole Richardson and Alex Webb’s work with the fledgling ski magazine Hardpack is really pushing the boundaries of abstraction, representation, and documentation in the ski space, as well an overlap with the fashion industry.

A particularly fascinating example is Frankie Carino’s (@canonfan2010) artworks being exhibited at the Arc’teryx Los Angeles store (Arc’teryx again, hmm). Carino shoots for Arc’teryx, but is this exhibition an advertisement, or just a use of the space to display Carino’s art? The products have not been moved aside, in fact, they intermingle with the works, their colors and shapes echoing and enhancing one another. Carino’s Instagram bio reads: “Los Angeles Material Based Conceptual Artist//Commercial Photographer”. His website has a whole bunch of sculptures and photographs, but his gram feed is primarily comprised of commercial work, for some of the biggest brands in outdoor sports, boarding, and skiing.

I guess this all makes sense, as the line between the commercial and the personal is all but disintegrated these days. We live in a world in which brand-association, affiliation, and loyalty is as much a part of our identity as our hometown or hobbies. We venerate brands and we aim to become one. Conversely, as economic uncertainty continues to lord over our existence, the price of “the good eggs” approaches $15 a dozen, can anyone be blamed for hitching their art-wagon to a commercial enterprise?

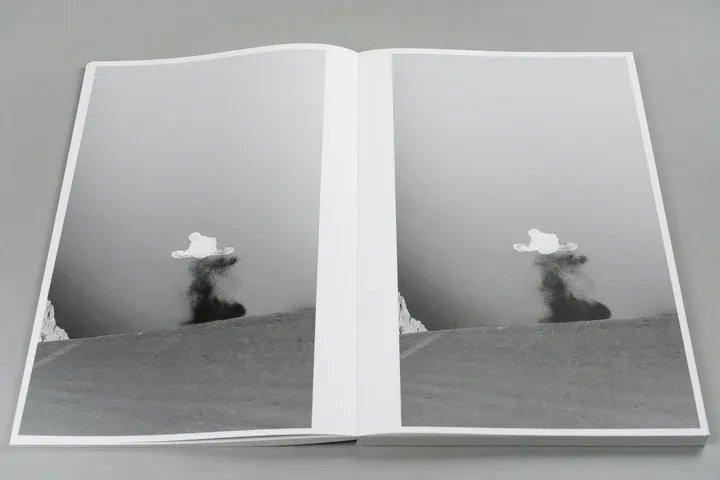

A final example I want to discuss is the photographer and artist Ari Marcopoulos’ recent snowboard-related work made in Saas Fe. His book “Black Snow” is comprised of 192 photos of a 3.2-second film clip of Haku Shimasaki performing a Cab Double 1080˚. The stills are desaturated and inverted, referencing the photographic negative, and therefore, according to the writing that surrounds this work, “linking the relatively new technique of multichannel video to the beginnings of photography.”

“Black Snow” is formally almost identical to Silvano Zeiter’s “Poly”, and aesthetically completely in line with much of the other work I’ve been discussing. And yet, Marcopolous’ piece exists almost entirely in the art space. The publication is disseminated by art book publishers and the accompanying video work makes the rounds at art-fairs and via Ari’s gallery representation. When written about, it’s a critique of the photographic medium, a reference to the historical photographer Eadweard Muybridge, and “a hybrid exploration of movement and time.” There’s no mention of what a Cab Double 1080 is, what the grab was, and why any of that would matter.

In the end, whether a piece of snowboard related media exists as “Art” seems to rely on a combination of display/dissemination context, creator intention, and an understanding of what “world” the progenitor of the work primarily inhabits. Further complicating things is a question of funding. If the work depicts a product that can be bought, and/or is at least partially funded by the “brand”, then is it actually just advertising, no matter what visual language it’s trafficking in?

Though Arc’teryx has figured prominently in the examples above, many brands seem to be on “board” (wink wink nod nod). The North Face, Mountain Hardwear, K2, and others have all been toying with these aesthetics and presentation modes in their events, advertising, and via their sponsored athletes’ content.

This begs a sort of chicken or the egg question. Is the industry (its brands, its athletes, its media practitioners) simply riding the wave of this aesthetic nouveau, or is the trend more calculated? In the face of climate change, declining population growth in developed countries, and ever increasing cost to participate in our sport, is there a concerted effort to associate these brands and activities with the “high culture” of the art world, and therefore gain access-to and affinity-with other luxury brands that traffic in this space? Maybe both of these things are true?

I’ll wrap up on an optimistic note. Ultimately, whether this work I’ve been discussing is “Art” or not, and whether or not the brands backing it have ulterior, less than “pure” motivations (I’m sure they do), what we’re seeing is an explosion of creativity and energy in snow sports media. One of my personal theories is that this style of working marks a dissatisfaction with the traditional still/documentary image and classic banger-trick clip. It seeks to communicate experience more fully, akin to how these activities feel, rather than just how they look. Furthermore, it’s obvious that still photography and long-form film have fallen out of fashion in digital spaces (see the rise of reels, Tik Tok, and Youtube shorts). In response, these works seek to reclaim space in the physical world by providing experiences that can only be fully understood in person.

It’s exciting, and inspiring. The possibilities that these artists(!?) continue to uncover is nothing short of an aesthetic revolution in this space. New forms, new feelings, new ideas are ping ponging around our world, and I can’t wait to see what’s next.

P.S. If you stuck around this long I want to address an elephant in the room/gallery. Almost everyone I referenced above are European and/or white males (myself included), or, colloquially, “Art Bros.” Obviously the snow and ski world is a very “white space” (still blows my mind that brand name made it all the way to market btw), but it would be nice to see things shaken up. I don’t reckon I can get sufficient distance from this to properly analyze it, but I also think completely ignoring it is a cop out. I will say that as these same demographics pervade almost all of skate/snow/surf/ski media, no matter how traditional or progressive, it seems to be a wider issue rather than something specific to this recent “movement.” I’m open to things being more intertwined than that though. Anyway, elephant nodded towards…