Remember that? Remember growing up in a time when pro snowboarders were rockstars? Remember back before Instagram when you could go about your day, open your phone, and not accidentally spoil the end to a video you hadn’t seen yet? Remember the way premieres were, too? A long video. What is it now? Well if you’re in Salt Lake, it’s two 10-minute videos and maybe a twenty-five minute flick a weekend, every weekend, between mid-September to mid-November. Snowboarding is a small world, yes, but it’s a world that’s been changing quickly—so quickly that a lot of the changes have come just within the past year. The number of videos being released is far higher than it used to be. Plus, with a few notable exceptions, the run time for these videos is more often than not declining. Why? Social media seems like the logical scapegoat, but it’s more complicated than that. Brands are changing where they put their money, and a lot of it is getting put back into their own projects.

Are these changes good or bad? Maybe they’re neither, or both. Maybe they’re just changes and nothing more. Maybe arbitrary concepts like “good” and “bad” only serve as relics to remind us of the world we left behind to go jib in the first place. If that’s true, then there’s one glaring question that comes up, what are we even looking at here? It’s clear that the entire snowboard video ecosystem is changing. How we fund, make, view and release footage is far different from how it used to be. The screen time is dropping, but the number of videos released onto the screen is growing. On top of that, it’s hard to make sense of all the factors that affect the snowboard video because change in the snowboard world happens so fast. It’s like trying to solve a puzzle, but the picture on the box keeps morphing into something else. A set of more important questions has now emerged. How did this happen and where are we at now?

The Era’s

Before we talk about brands, budgets, and everything else that makes snowboard videos such a complex topic, let’s define what we’re talking about when we say full-length. For the sake of this article—and since there’s no actual definition out there (thanks Webster)—let’s say full-lengths are anything over 30 minutes, give or take. And full-lengths have parts: people riding in their own section of the video.

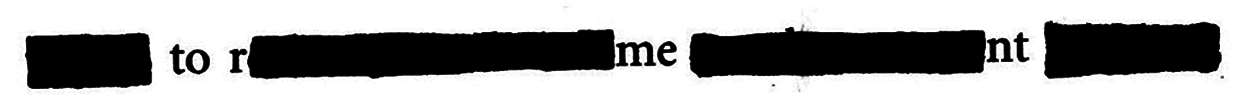

It’s also important to talk about how all of this started. Dating as far back as the early 90s, a time when skateboarding still held its edge, filmmakers began to pull inspiration from skate videos and apply it to the mountain. At this time, filmmakers such as the Hatchett brothers of Standard Films and Mike McEntire of Mack Dawg Productions picked up cameras and began working on their first video contributions to the snowboard world. It's worth noting that snowboarding was still in its beginning stages at this time. Riders were figuring out how to ride switch, how to change their stance, and how to use the flex of boards for butters and tricks.

“Up until 2001, majority of the stuff that you shot was on the mountain or just off the mountain,” said Rob Whitey, creator of Kingpin Productions.

This can be seen in some of the most seminal videos from this era including Pocahontas (1992), Sexual Chocolate (1994), and the famed Subjekt Haakonsen (1996), which captured snowboarding in the most relatable fashion, on the mountain.

Some of the first street clips in snowboarding can be found as early as 1993, in videos like Mack Dawg’s The Hard the Hungry and the Homeless, and Upping the Ante, released just a year later. But it wasn’t until the late 90s when videos like Decade (1998) and The Revival (1999) really started to push the envelope of what could be done outside of the resort, showcasing riders like Mikey Leblanc and JP Walker, who pioneered the way for street snowboarding. From there, things started to catch on, and entered a new era of snowboard filmmaking which not only brought us Forum Snowboards’ 2000 classic, The Resistance, but also introduced us to some of the most well known crews of this era: Absinthe Films, Think Thank, Finger On Da Trigger, and Misschief Films—one of the first production companies (alongside Chunky Knit Productions) to feature only women in their movies. This was also the same era that introduced us to the illustrious Brain Farm Productions and their debut film That’s It, That’s All (2008), marking the start of this crew’s mission to film the most high budget backcountry snowboard films of that time. It didn’t stop there, either. Throughout the early to mid-2000s, filmmaking became more accessible and the amount of videos being released each year multiplied from what was seen in the past. At the same time, brands became more interested in self-producing videos that featured their own team, which brought us some of the first full-length projects from brands such as Burton, Capita, DC, and Stepchild.

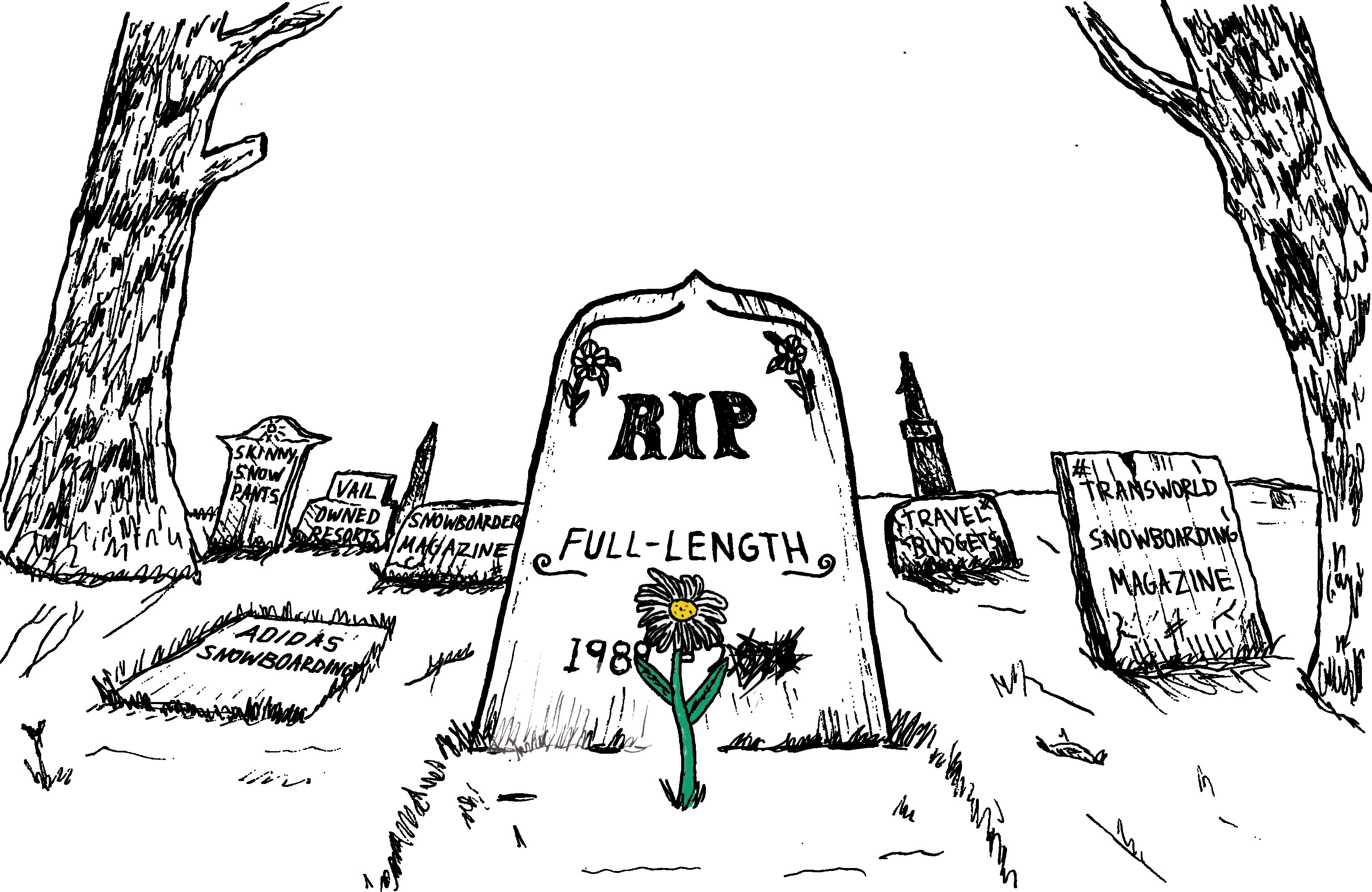

In 2010, Videograss entered the scene, beginning yet another era in snowboard filmmaking. The self-titled debut full-length film, Videograss set off a series of videos that would forever leave an unmistakable mark on snowboarding. And while veteran film crews like Kingpin and Mack Dawg began to fade away, the films from this new, post-2010 era grew, bringing in some of the most beloved films of the decade. Keep the Change, Chikenmeat Unlimited, and The Uninvited all made their mark during that era. Team videos were also on the rise during this time. Cult classics, Adidas’ 3:00 AM (2016) and Vans’ Landline. (2018), graced our screens during the latter part of the decade.

Now we have reached the age of…well…perhaps an identity crisis. It’s a time where the majority of current videos do not exceed 30 minutes, and feature only a select handful of riders. Think Good Sport (2021), or perhaps How Dark Blue Feels released the same year. Both films feature a relatively tight knit crew of riders with similar preferences on what they like to ride, different from the large productions that had existed in the past. There has also been a rise in individual part videos which heavily emphasize one rider with a few supporting cast members—Blender (2018) featuring Tommy Gesme and friends, and living room (2021) featuring Cole Navin are two examples of this. Simultaneously, in these past few years we’ve seen rapid increase in the amount of young individuals getting involved in snowboard filmmaking with crews like The Dust Box and Panic Order paving the way for their generation. However, this year—2023—we’ve seen something strange happening. We’ve seen a resurrection of longer format projects. Knight’s of the Brown Table, Rated R, and Clips to Chill/Relax to are all returns to form: 40+ minute projects with distinct, individual parts. The rise of full-lengths in the past year appeared seemingly out of nowhere. Why, though? Was it nostalgia for the past? A rebellion against the present? Maybe. But it’s impossible to understand the return without breaking down the decline.

Brands and Money

So, how did we end up here? From 35,000 feet it’s easy to jump to conclusions. Instagram, of course. We’ve been jaded. Our attention spans are shorter, full-length videos don’t carry the same weight, and our need for instant gratification takes precedent. That’s true, in part, but there’s more to it. The money coming into snowboarding has changed and filmmaking is more accessible. Everybody has a camera on their phone and more people are making videos. Snowboarders are dispersing and it’s harder to get 10 riders involved in the same, year-long project. It seems social media, the readily available scapegoat, is far from the only force pushing change in the snowboard world. It can be challenging to recognize, either as a rider or auteur, the influence these factors have when they themselves are engulfed in it.

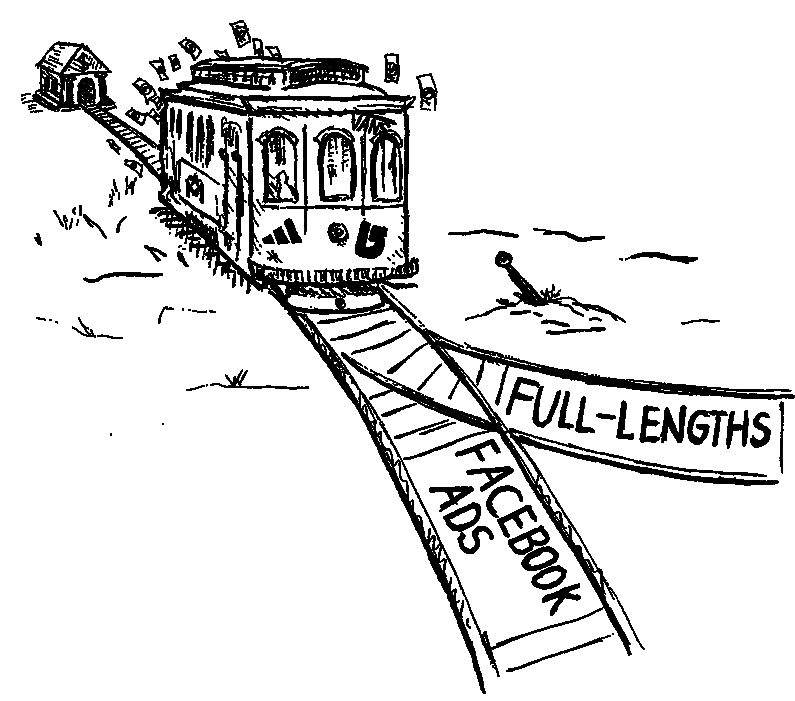

To start, company buy-ins for videos still happen, but they’re not as prevalent as they used to be. For the most part it’s no longer financially sensible for multiple companies to support the same project. This changing strategy has metastasized into more than just business. It has restructured everything. It is the driving force behind so much of the change. More than Instagram or anything else, it all comes back to this restructuring.

“Brands would spend all this money and then not see any sales back from it. Then they’d be like, ‘why are we spending all this money to have our logo next to another brand that sells the same gear?’” said Ted Borland, filmmaker behind the full-lengths Everybody, Everybody and Tangle. “That’s definitely a big contributor to why there’s no money in snowboard videos anymore. Single brand videos could solve that.”

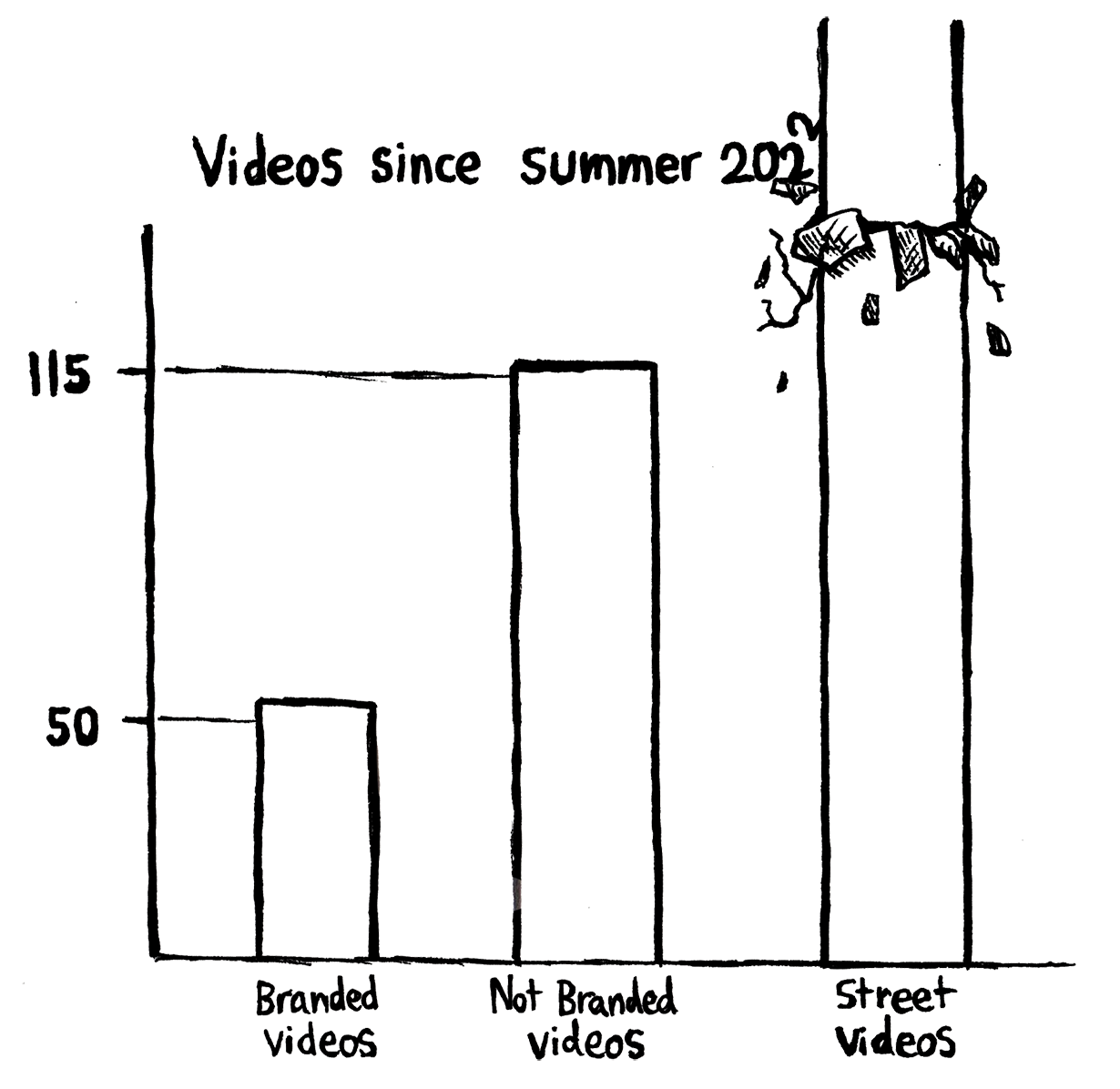

So, the companies who shifted the digital zeitgeist now have the power to reshape it. And it seems like they’re starting to. Individual companies are now spearheading smaller, individual projects. Since the summer of 2023 [more videos have/will continue to come out in the time between the writing and publishing of this article. This, however, is our count] 161 videos have come out1. Of those 161, 31 were branded videos. When we say branded we mean one company is “presenting” a video. Think Burton’s Blooom or K2’s Orange Things. That means 130 were not branded. This doesn’t mean there was no support. There was. Videos like Needed You or Sixth Sense aren’t branded videos but they still get support from brands. So what? Well, now we can see the shift in where the money is going. Brands are funding their own videos as well as supporting smaller projects. This is a change from a select few riders getting buy-ins for big group full-lengths.

There’s also something interesting when you look at the length of videos. Of those 161, only five exceeded the 30 minute mark, qualifying it as a full-length under our definition. Compare this to the 2003/2004 season2. Of the 8 major films released then, only two ran under 30 minutes3. And it was just barely, Thunk and Chulksmack came in at around 29 and 28 minutes respectively. Six videos to five wouldn’t be a substantial drop if 160 videos came out in 2004. There weren’t that many though, there were eight. That means in 2004 75% of videos were full-length videos. Today, that number is 3%.

In this new era, videos like Ride’s Rated R, Mt. Mtn’s Cool Clips to Chill and Relax to, and Brown’s Knights of the Brown Table do exist as full-lengths. They exist among all the other short videos that are still being released for the 2023/24 season. Vans, once on the forefront of the modern full-length, released Bless The Ledge / Secret Tape, a nine-minute video fit for the current ecosystem. K2’s Sweep was five minutes and even 686’s Atlas, another two year project, is a fraction of the length of the Brown or Ride videos. It’s interesting that of the three videos, one was branded and two were not. It’s easy to assume why Ride made a video. Objectively, they have one of the best teams in snowboarding. Why not put them all together. That makes sense. But for Mt. Mtn and Brown, try to understand the intention. Why create an hour-long video in the modern age, an age where viewers are simply not used to that.

“A longer format video gives riders a certain place and avenue to create something that will stand the test of time within snowboarding,” Brock Nielsen, Brown’s director, said.

There is truth to that. Set apart from the plethora of twenty minute or less videos are five videos from this year. And frankly, most of the videos worked. The Brown video has over a hundred and eighty-five thousand views on YouTube, a stunning rebuke to any naysayers. It might have been risky putting aside two years to film a video, three in the case of Mt. Mtn, but all videos did what they set out to do: make something people enjoy and are inspired by. It is the same end goal for anybody who is creating a snowboard video.

“That’s the whole point of making these,” Nielsen said. “To make you feel something in your gut or your heart and then make you want to go out and create and do positive fun things with your friends.”

However people perceive those full-lengths, they are still not the norm. Videos are now not usually over half an hour. When people talk about why these videos are getting shorter, they talk about social media and, inevitably, attention spans. However, this theory has been at least partially debunked by the release of all these full-length videos this past Fall.

Really though, it’s all about the market. Social media killed the market… kind of. It killed a market. It killed the dvd sales market. But it also created a new one. Instagram puts, depending on the size of the company, thousands of eyes on products. Sure, all those shorter brand videos came out on the internet at no direct monetary cost to the viewer, but there is still some cost. If the short brand videos are effective, then people will go out and spend money on certain products. Videos still cost money these days, it’s just less direct.

The Riders

The market Instagram created isn’t just for brands to promote products, it’s for brands to promote riders. Arguably more important though, it’s where riders promote themselves. Videos used to be the only avenue to get snowboarding into the eyes of riders everywhere—that’s all changed. Now snowboarding has gone mainstream, for lack of a better term. As much as people want to hold onto the past, it’s simply not feasible. The boarders who appear once-a-year with a new part don’t resonate as deeply with the broader snowboard audience as say a Zeb Powell or a Jill Perkins. Yes, Zeb and Jill do film, but they do other things too. Obviously, it’s not realistic for every boarder out there to get a Wendy’s commercial, but there’s a middle ground. Like it or not, self and brand promotion through social media is the new norm in snowboarding.

“It is THE platform, so it is more important to the value of a rider and their sponsors,” said Mack Dawg. “Adapt or die man.”

Adapt or die is a sentiment most companies have embraced head on. Some borders feel this way too. Many of them find Instagram easy, they live and breathe marketability. There are a large number, on the other hand, who don’t. As cliché as it may sound, snowboarding is counterculture. No serious snowboarder started snowboarding to become marketable and famous. It was probably the opposite. It was an escape. Snowboarding, for so many snowboarders, was counter to those everyday mundane factors of life. Now, everything is changing.

“What do you want? Do you want to be a pro snowboarder? Because being a pro snowboarder means having people see your snowboarding. If the only avenue you're using is a video part or a snowboard video, then you’re kind of not using all the tools in order to do the job and you’re kind of not going to be a pro snowboarder unless you’re just God’s gift to snowboarding,” said Borland. “It’s your album. It’s a snowboarder's album basically, is their video part or their short video. But, unless you’re on the radio, no one knows your album is coming out.”

This can be hard for those people in the middle. The majority of boarders aren’t “God’s gift,” but a lot of them are great. People like that can struggle to break through when social media isn’t for them.

“You can’t just have good style, good trick selection, and good tricks,” said Justin Meyer, creator of the production company Videograss. “You kind of have to be a face, and a person. You have to put yourself out there—and maybe you didn’t want to.”

There’s an opposite side to that coin too. Instant gratification is a huge factor as to why people post. It has transcended brands asking riders to promote products on Instagram. Riders are posting for themselves. But having a constant internet presence can come with drawbacks.

“That’s just the nature of the world we’re in nowadays. It's not about the best, it's about what's the newest,” said Whitey. “You know, satisfying a need at this very moment in time. But usually the problem with that is the things satisfying the need right now are not things that anyone tends to care about ten years from now.”

That immediacy also spawns trends out of thin air.

“What the snowboard video to progression was, it made progression a lot slower. Not just tricks but trends, you’d pick up on a trend that builds and has time to develop,” said Meyer. “Nowadays kids pick up on trends in 10 minutes and they can run with it when it never had time to develop. They don’t even realize it’s whack before they’re running it.”

It’s not just trends though. This is happening with tricks too.

“You used to almost have to study a dvd or vhs and really learn, visually, new tricks,” said Meyer. “Where now it’s just a new trick happens and you see it right away. It’s sped up progression, but maybe not for the best. I think maybe it’s better when people have time to simmer on it for a bit.”

While the community may be affected by the trends that pop up, it ultimately falls back on the rider. The instant gratification trade-off may not be worth it when people are biting your style.

“In a way, if you think about it, if you are a rider and you’re progressing and doing some shit that nobody else has quite done, by putting out something you’re almost doing yourself a disservice. Everyone else is just going to copy that shit right away.” said Whitey.

Has The Time Come?

It’s hard to overstate how fluid snowboarding is. What’s cool today won’t be cool tomorrow, and that thing from yesterday you already forgot about, that will be cool again next week. Now—today—is maybe the strangest time in snowboarding. Never have there been so many eyes on the sport and never have there been so many differing takes on it. Even in that last sentence, the word sport will probably spur some sort of debate with whoever you’re sitting next to while reading this. Eyes though, don’t necessarily translate to budget or support. At times, it feels like the world is watching us and other times it feels like we have to go at it alone. So, it seems any question on the full-length—is it alive, is it sustainable, why have we shifted—should be prefaced by some sort of reminder that everybody who’s here is just trying to do the same thing. Prefaced may be the wrong word, this feels more like an epilogue.

Whatever it is, it shows the durability of snowboard videos. Videos will always be made. The form may change, it may ebb and flow. Trends will take hold and videos will almost certainly follow those trends, but they will still exist. They’re a constant, perhaps the only constant in a world that’s changing so quickly. The video’s importance and resilience is only magnified by changes in the industry, not negated by it. It’s magnified because throughout shifting media platforms, through Instagram and TikTok, it still exists. Through the shifting flow of money, the video still exists. The video is a non-negotiable part of snowboarding, we won’t go forward without them. We aren’t able to go forward without them because that’s where the expression comes out. We can’t stay bottled up. We won’t survive. This all seems to echo Brock’s statement from earlier which is worth repeating in full: “That’s the whole point of making these, to make you feel something in your gut or your heart and then make you want to go out and create and do positive fun things with your friends.”

Illustration by: Jack Estenssoro

1. The list of 175 videos was compiled from Jeff Holce’s 2023/24 video playlist. There were two omissions from that list. The first was because a video was both ski and snowboard, and the second didn’t fit in the date range we laid out.

2. The list of 8 videos came from the site Snowboardingfilms.net, which compiles videos by year.

3. Runtime for Pirate Radio was unavailable. It may have also ran under 30 minutes.