2025 Yeti Natural Selection Tour Championships

Revelstoke Mountain Resort, BC, Canada

I quit writing about snowboarding six years ago. The following season, Natural Selection debuted in Jackson. I was there that week, relieved to not be holed up in a hotel on my laptop. Yet, here I am, relapsing in a room I can’t afford at the base of Revelstoke.

Looking around at what’s happened during my half-decade hiatus from keyboarding about snowboarding, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to call NST’s presence the most impactful addition to the sport. That descriptor is operative because art’s intent isn’t to be judged quantitatively. Snowboarding as art happens via films, magazines, and other media mediums. Sport happens in competition, and we didn’t come here to pontificate film burns and song choice—though I’ve appreciated the nods we’ve seen to soundtracks from Brain Farm films, including Sage Kotsenburg’s choice of M83 as his walk-on song during rider seeding.

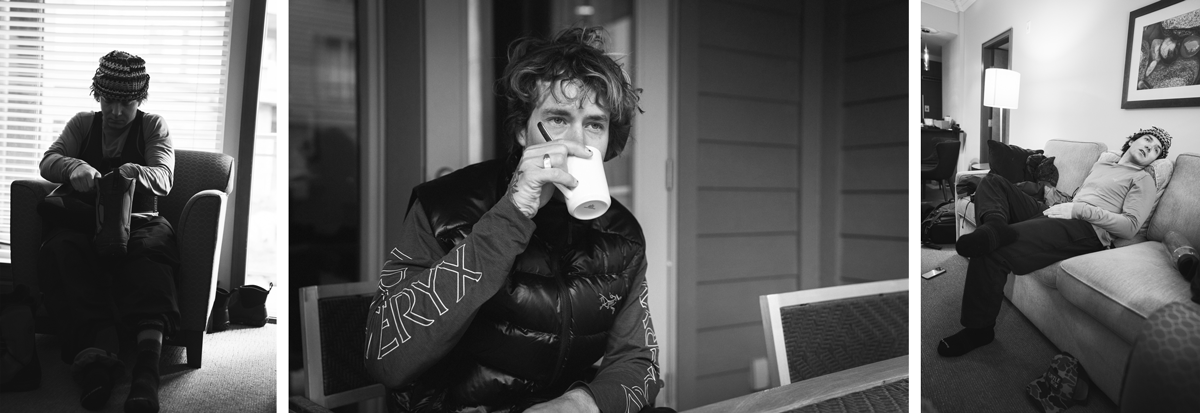

We came to Revy to watch people compete, and behavior observed from competitors leading up to the contest logically looks like that of athletes more than artists: abstaining from alcohol, hitting the gym, going to bed at 9:00, obsessively studying footage and plotting lines, playing mental games with one another. While some of the stoney camaraderie touted during televised competition is rooted in reality, we don’t have to pretend professional snowboarding is good times all the time. However, it’s important to note a critical separation between NST and something like the X-Games or Olympics: riders are not confined to a predetermined set of features, and line choice adds an element of expression that traditional event formats don’t have.

Of course, when something involves points, it benefits a competitor to understand how they can score the most. In team sports, this is simple and binary. Points are gained by moving an object into or through a defined space—baskets, goals, end zones, etc. In judged competition, there’s nuance and no such thing as perfect judging. It’s inherently impossible.

NST judge Jussi Oksanen sums up the event’s judging formula, “They call it CREDO: Creativity, Risk, Execution, Difficulty and Overall. The score is [a combination of] all of these versus points for each of these categories.” On one end of the NST spectrum, we see riding that could be explained as slopestyle in powder. This is why there are man-made features on the course. Special shoutout to Revy loc’ and NST competitor Dustin Craven and the team of builders for crafting these in the off-season. I don’t have a great descriptor for the style of riding that happens at the other end of the range, but it involves less spins, bigger drops, and more technical lines. Perhaps time-tested terminology, freestyle and freeride, best sums up the spectrum so silly as it may sound, I’m running with it.

Logically, judging seeks to favor those best able to blend these two genres. As a viewer, what makes NST especially engaging is observation of individual approaches to a venue such as Montana Bowl, just out the gates of Revelstoke Mountain Resort. Standing at the bottom of the lower face, a particular diving board-esque feature presents itself prominently. Something you might mind-surf or joke about. In fact, I asked aloud when we got to the venue, “I wonder if a skier would be crazy enough to hit that.”

Qualifiers saw a new and non-bracketed format this year, beginning with 24 total riders, half securing a spot in finals: eight men and four women. Topic for another time, but it would be awesome to see an even amount of competitors between those categories in the future, and what Robin Van Gyn is doing with RND is an ideal catalyst for that.

I was psyched to see Brin Alexander snag a spot in the event and bring the DOPE crew with him. To be clear, we’re talking about the legendary Canadian crew, not a shitty outerwear brand. The Whistler-based wildcard—my definition of the term, not NST’s which turned out to be Gigi Rüf—drew first drop in seeding and opened the contest by skydiving off the aforementioned feature. It was, without a doubt, the largest drop I’ve ever seen someone attempt on a snowboard. This set a tone that would carry through qualifying into finals. I should also note that Brin attempted a front 3 melon off this same drop on his second run.

With a new qualifying format, it quickly became clear that safety runs wouldn’t advance riders, and an absolute Hail Mary of a back 3 from Jared Elston—off a natural takeoff into a sniper pocket that he skimmed and somehow pulled out of—was a hallmark example of how to navigate this contest from the perspective I’ve deemed “freeride,” for lack of a better term. Perhaps the other most notable example of this tactic came when Elena Hight held a frontside grab long enough to warm the base of her board off a massive drop on her second run. As NST judge Leanne Pelosi explained to me, qualifying scores were relevant to a specific round and not intended to be compared across heats, i.e. a score of 80 in one round does not inherently indicate that the run was superior to that which scored 75 in a different heat.

With the finals day format returning to the event’s hallmark bracket system, strategy shifted slightly, allowing riders to tailor runs per round primarily based on beating a singular opponent, ultimately hoping to advance until a final faceoff, deciding first and second place. On finals day, however, scores were relevant across rounds, as they dictated ultimate placement. Visibility was consistently low, in contrast to qualifying which saw everything from blue sky to full fog. This provided a relatively even playing field, for the most part—equally challenging for every rider working to navigate technical terrain in low light—but didn’t deter a display of some of the most impressive powder riding I’ve witnessed. The final bracket in the women’s event saw two of snowboarding’s most prolific figures, and Arc’teryx teammates, Spencer O’Brien and Elena Hight, riding head to head. On the men’s side, a newer name was pitted against an established one, as Blake Moller and Stale Sandbech battled for the podium’s top step. With individual techniques on display, it does seem a freestyle approach was rewarded, and Spencer and Stale took it. The magnitude of riding in these rounds was absurd. It was across the entire contest.

Until NST’s advent, this level of snowboarding was really only visible through film parts. To be with a professional film crew in the backcountry is an incredible experience that a small fraction of snowboarders will have. NST turns a featured face into a stadium, allowing the public to watch, for free, 24 of the world’s best riders—some of whom ride together regularly and others who never would otherwise—dropping, one after another. If you can’t make it to Revy, you can watch live at home. This formula has served sports since the invention of the television, bringing with it attention and revenue. If you want those things for snowboarding, NST is inarguably of benefit to the sport.

The progression of NST represents a pattern of Travis Rice’s career: escalation through serialization. We first saw it via films, beginning with That’s It, That’s All and culminating with The Fourth Phase. You can argue in the comments that it started with Community Project and continued through Dark Matter and subsequent shorts, but, point is, the guy knows how to execute a vision seen through those piercing blue eyes. This year, NST felt bigger than ever. Its execution was refined, and it showed in the riding we witnessed this weekend. The team behind the scenes is a small one capable of delivering something outsized.

While good vibes and high fives projected to the masses are sometimes a facade masking more competition behind the scenes than we’re willing to admit, opposing teams don’t party together after a championship game, and Saturday night spilled deep into Sunday morning, with many competitors dancing to house beats on a champagne-soaked dance floor. What went down over the days prior is reason to celebrate. Snowboarding is a good sport.

Results