Story by: Keenan-Faulkner Cawley

Photos by: Erik Hoffman

Illustrations by: John Garoutte

“Snowboarders, Grandma!” Little Astrid was squealing, nearly convulsing on the carpet before her grandmother.

“They-they were – it was me and Elsa and Hedvig playing Snow Queen at recess and then-then whoosh!” She makes a gigantic twirl, collapsing back on the floor. “The snowboarders were flying!”

“Are you still on about those lunatics?” Mother yells from the kitchen over a hissing stove. “Yes! They had ramps and-and shovels! Cameras! They-they were making a movie! Grandma, it was fantastic!”

“It wasn’t fantastic,” Matthias chimes. “It was cool!” He tries matching the tone of the sacred word. “And they’re not called ramps – they’re jumps.”

“Right,” Astrid remembers. “Jumps. And the railing! Whoosh,” she tumbles again. “Gliding down the railing.” Again, her older brother corrects her. “It’s called a railslide, idiot.”

“Matthias!” comes the parental scorning. He mumbles an apology. Astrid takes it in stride.

“And-and there was a girl, too! Whoosh! She was so –” She looks to her brother. “Cool!” Grandmother delights at their excitement.

“You know, that really does sound fantastic.”

“Oh, it was! I loved it, Grandma! You wouldn’t have believed it!”

“What you may not believe…” The old woman leans in close to her grandchildren, “Is that I, too, saw the snowboarders.” “Really?!” both kids say in synchronicity.

“Yes. Just yesterday, when I was taking Sirius for his little walk through the courtyard.” This makes Mother’s eyebrows wriggle from the kitchen. She stops her cooking to poke her head out.

“It’s true, Maria,” she says to her daughter-in-law. Then, back to the kids, “I was getting ready to take Sirius for his walk and when I opened the door, I was met by this massive mound of snow – a hill, really. Sirius tried pulling me up it but I stood awe-struck. Confused – bamboozled!” she gets a rise from her miniature audience. “I was out there not four hours prior and there was no mountain of snow. The snow’s been melting all week, after all! But I was shocked at the sight. And I must’ve been wearing it all over my wrinkly face –“

“Aw, Grandma!”

“Because the next moment I was approached by two young gentlemen who painted the picture for me. They had moved all that snow and made a hill out of it – a ramp.” She pinches her granddaughter. “And then one goes up it, and then…”

“Whoosh!” goes her granddaughter.

“Comes flying down and soars, spinning like a helicopter onto the railing!”

“You saw them doing the railslides, too?!” Matthias asks.

“Yes, my dear! I saw it all. The railslides, the lot of them marching around with their shovels –“

“Did you see the girl?” asks Astrid.

“Yes, Astrid. And how kind she was. I’ll admit, I was a little apprehensive; the sight of them with all their equipment was strange to say the least. But they were just friendly as could be to me and Sirius. The girl even escorted me over the snow field they’d placed on the walkway. I was amazed by them, really. All that work they put in, and the marvelous talent, obviously. But you know what was the most remarkable?”

“What, Grandma?”

“There was a photographer with them, and for some reason, when I saw him, all I could think about was your Uncle Ulrik.” The children process this quietly.

“You know, he was a photographer,” Grandmother adds.

“Really?” Little Matthias asks.

“I miss Uncle Ulry.” Astrid interjects solemnly.

“Don’t we all.” Her eyes begin to gloss over.

“That’s enough,” Mom chirps from the kitchen. “Dinner’s almost ready.”

“Right,” Grandmother says, shifting gears. “Well, you said it Astrid – they’re with that company making a movie. ‘666’ or something.”

“C’mon Grandma, it was six-eight-six,” says Matthias. “Which reminds me…” He goes for the iPad. “I got a link from them!” He hops on the couch next to Grandmother. His sister follows. He pokes around the screen. A dog appears, barking on the rubble of a burned down house. The kids don an English accent in the dawn of action.

“Good sport!”

“Cheerio, good sport!”

“Old chap!” Then there’s action.

“Hey, that’s the guy!”

“Wonderful!”

Then, abruptly, comes the screaming. Mom barges in.

“Enough of that!” She snatches the iPad and scrabbles around the screen trying to turn it off. “If your father came in and heard you listening to that…”

“Oh dear,” Grandmother defends, “you know he used to listen to that music all the time.”

“But your son doesn’t want his children listening to it.”

“Aw Mom, it was just gettin’ good!”

“I’m not going to say it again.” She finally stops the movie and chucks the device. “We’re not bringing the spirit of Daahl into my house. Now come set the table. Your father will be home any second.”

Father enters the dining room. His children wait, fidgeting in their chairs. His wife takes a slow sip of white wine. His mother blows gently on a cup of tea. Steaming plates of fried fish and rice sit before each of them. His daughter and mother both receive small affections. The son gets a light scruff on his blonde head. He sits down next to his wife. She gets a hand placed on top of hers.

“This looks great,” he says. In reality, it looks extraordinarily bland. She pours him a glass of wine. “Dig in.”

His son all but dives in head first, the food rapidly vanishing. His daughter picks at it. His mother slices fish fragments delicately. His wife ambles butter along a piece of bread. He refrains from dumping his wine on the plate. ‘Fish soup à la Chardonnay’, he thinks. ‘It would match, all plain yellow. Old white. A shallow pool of plain yellow mercury. It would make no difference’. Which is why he opts out. Save the drama, though drama is in the same vein of what he longs for. He pours a healthy splash of wine down his throat. The light clinking of tableware and plaintive sounds of chewing act as a metronome for his mind. He looks out the window, beyond his family, and notices it’s beginning to precipitate. All the muffled noise mesmerizes him.

His daughter breaks the spell.

“Daddy, can I get a snowboard?”

Her brother kicks her underneath the table then buries his head in the remnants on his plate. Grandmother sets her utensils down and blots her lips with a napkin. Maria inhales her wine. Father chews for a moment, then answers.

“A snowboard, huh?”

“Yes, daddy, I want a –“

“The kids saw some snowboarders at school today,” his wife says.

“Is that so?”

“Yes, daddy, and it was fantastic!”

“Marvelous.” Grandmother winks.

He goes on chewing so Astrid goes on talking.

“Really, daddy, it was! They were flying and jumping…” She acts these out from her chair. “And railsliding! And there was a girl snowboarder, too! Daddy, they were so nice and-and –”

“They really were,” Grandmother says.

“You met these snowboarders, too?”

His mother nods behind her tea. “Just yesterday. They were at my apartment complex.”

“…Snowboarding?”

She gives him the spiel.

He chuckles to himself idly. He downs what wine was left. Everyone at the table knows to stay quiet. He mulls over the fish on his plate, examines the empty glass. He looks beyond his family, out the window again. Snow falls softly. It wafts past the window. Just a flurry, no doubt, but still: some spring. Even for the coastal city of Trondheim. The ocean plays mysterious games with the weather. He wishes it would make up its mind already. He refills his glass.

“You know your uncle – my brother – he used to snowboard.”

“Grandma said he was a photographer!” his eldest exclaims.

“Well, yes, he was more so a photographer.” He swirls the wine around. “But he snowboarded too. Only a handful of times, but, still. You remember, Mom?”

She smiles a grandmotherly smile.

“He came back one time – his whole ass black and blue!”

“Honey!” Maria says.

The kids giggle.

“It’s true! The whole thing –” He stretches his arms out wide. “Bruised to hell and swollen like a pumpkin!” The kids’ laughter makes him even more cheeky. “But I’ll never forget the smile on his face when he showed me…” He realizes that he had forgot.

“Did you ever go with him?” Astrid asks.

He shakes his head, gulps his wine. “He tried to get me to go with him…” He actively remembers. “But it was during training. Boot camp at the academy. I wanted to but…”

The room is attentive. Ulrik, breathing or not, always had that power. More wine gets drunk. “But after seeing his purple rear-end, I figured I should opt out.”

“And probably for the best,” his wife adds. “I mean, at that time – it wasn’t two months after you finished boot camp that we got pregnant with you.” She glances affectionately at her son. “Lord knows what would’ve happened if your father hadn’t graduated.”

The man studies his glass. His gaze moves naturally to his mother’s. “Lord knows…” he mumbles. Each body at the table is too full of thought to speak. Dinner ends restively. The man closes the children’s door. He meets his wife in the hallway.

“Did mother leave?”

“I just saw her out. She had to get home to Sirius. More walks, more meds... She said to tell you she loves you.”

“I’m glad she came over.”

‘Are you?’ she wants to ask. ‘Because it seems you could’ve just as happily gobbled your wine and riled the kids up without her being here’. But she bites her tongue. “Yes,” she says robotically. “It means a lot to her. And the kids.”

He nods, ambling to the living room.

“Did they go down alright?”

“Mhm.” He collapses on the couch. She changes her mind. “Not too riled up from all that snowboard talk?”

“Ha.” He finds the television remote.

“I assume if you get Astrid one you’ll have get one for Matthias, too?”

“I mean –” His finger hovers above the red power button.

“Those things aren’t cheap.”

“They can share one.”

She fakes a laugh. “I’m not sure if you’re seeing the bigger picture.” He drops the remote and looks at her. His eyes say ‘just say it’.

“Do you really think this will fix things?”

A long breath escapes his nose, and with it, too, goes his attention. She soon disappears and he’s alone on the couch. The television whispers some sports highlights but he’s listening, somewhere between capacity and null, to the indecisive weather pitter-pattering on the roof. If only it would clear up out

there, he thinks. Maybe then I could get my life back to normal.

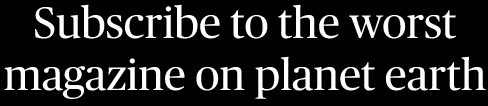

The wipers start squeaking across the windshield. I turn them on low.

I drain the last of my coffee. Øivind, the new recruit sitting shotgun, does the same. He’s about to talk, I know it. One week in and I can already read him like a book. He’s about to say something about the weather. With what little I’ll offer him on that topic, he’ll begin inquiring about what I think we’ll be getting into for the day. The job at large. Life. My lack of enthusiasm will incite anxiety palpable to only him. He will become uncomfortable. He’ll want a smoke and I guarantee he’ll use the premise of getting another cup of coffee to do so. He’ll light one up the moment we get out of my car.

I flick the wipers back on high.

“Some spring we’re having, huh?” I exhale out my nose in agreement.

“Look at that, switching back to snow again.” He fiddles with his empty cup. “At least it’s seeming like it wants to…” He cranes his neck forward to gaze out the windshield. “Lookin’ like there’s a little blue up there.” He stays leaning over the dash for a moment before finally relaxing back in the seat. “What’s the temp?”

I look between my fists. “34.”

He’s about to say ‘ah, shit.’

“Well, shit.”

Close enough. The wipers go back on low.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned about weather, it’s that it will only feel nice for so long. A storm is always building. It’s not that complex. When the ocean is calm, when placid waves lap the shore, expect turbulence. When you follow a blue sky all the way to the horizon and notice it’s the same color as the sea, you’ll realize that it’s not blue; it’s gray. And soon you’ll find that everything is gray. No duty can go unbroken forever. There will always be a lapse. That’s the only ritual you can count on. Simple. And a storm will last as long as it does. A cold spell stands behind a warm front in queue. It’s just the nature of things, the nature of nature.

The wipers go back on high. Øivind’s been speaking, but fuck if I heard any of it. It’s only that I can tell he’s repeating himself that garners my attention.

“Do you even know?” he asks.

“What?”

“Where we’re going.”

“Of course I do. Heimdal.”

“What’s in Heimdal?”

I should tell him about last night’s report. How some old lady called in to complain that people were standing in the tracks at Heimdal Station. That they were shoveling snow from the tracks to the platform. That the conductor had to switch the lines and redirect travelers to the platform outside of the tunnel. That it took officers nearly an hour to get to the scene and reprimand the offenders. That the offenders were snowboarders; that they’d built a ramp on the platform so they could ride their snowboards down into the tunnel.

But all of that would send Øivind into a relentless barrage of questions. That, I could live without. Especially considering we’d be there shortly, and given that the report was from last night, it’s not like these snowboarders would still be around. I suppose I just want to see for myself. The road drones me out. Øivind snaps me back.

“Well, Captain?”

“Coffee,” I say. I point to his cup. “I know a great café there, right next to the train station. Figure we’ll go get you another cup.” The wipers squeal across the windshield in front of us. I return them to low.

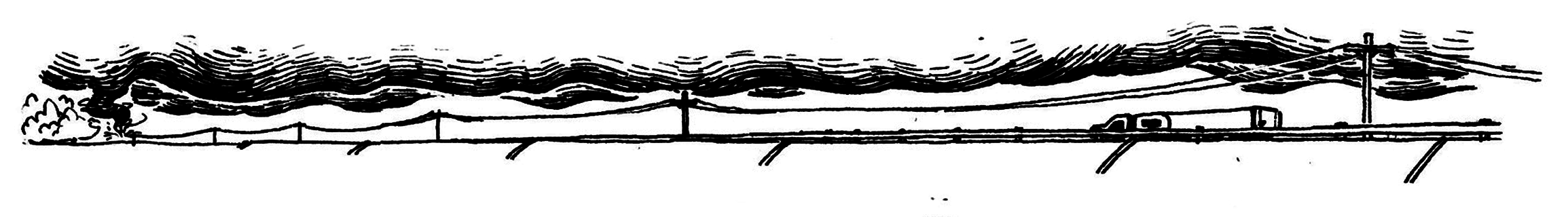

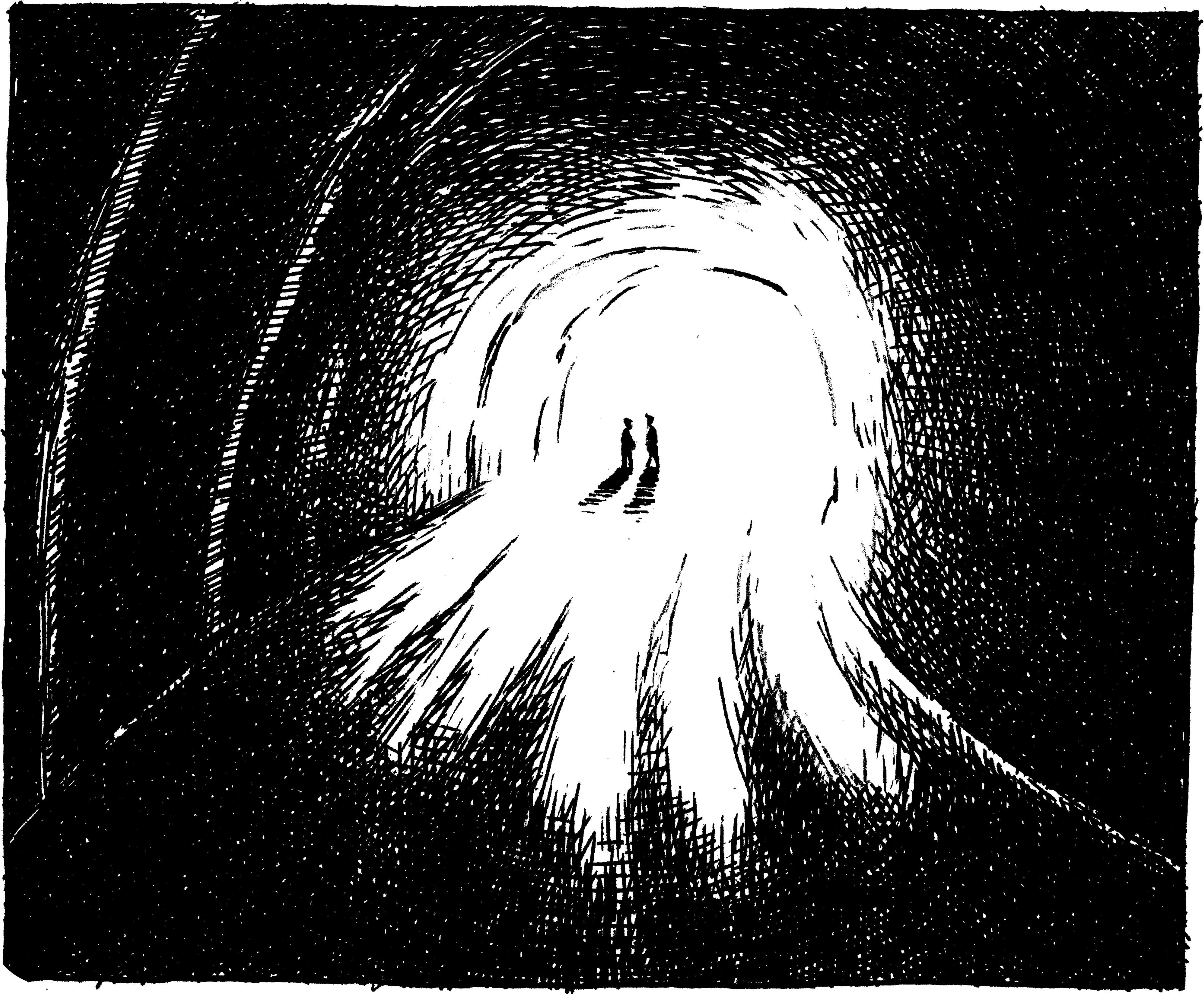

It’s a busy morning in Heimdal. We wait 10 minutes in line for coffee. Øivind makes for his cigarettes but before he can get them I join the lot of pedestrians and head into the western entrance of the station tunnel. It isn’t until we’re underneath the tracks that Øivind gets it lit. The lighter flicks echo. I notice a strip of snow on the other end of the tunnel. A man helps a mother carry her stroller through it. I hear Øivind slip on ice behind me.

“Careful.”

“Yeah, yeah.”

I look right and see the stairwell that leads up to the center platform. On the cusp of my instincts driving me up them, calamity strikes. The reverberation carries down the tunnel. It makes Øivind shutter.

I don’t know how I know but I know. I can’t tell him though. He looks bewildered, nervous. I’m excited, albeit anxious. I nod towards the noise and start walking.

50 meters to the gateway: silhouetted civilians amble to and fro.

45: One in particular is crouched by the entrance. He’s tucked in a ball.

40: He twists his head in an awkward position. He’s looking into a viewfinder of a small camera. Another man walks over to him, laughs, then walks back to another camera stationed on a tripod.

I tell Øivind to tuck his badge. He looks at me, head tilted like a dog. We’re not here to arrest anyone. I don’t want to make them nervous. Any indication of authority can skew an interaction or story. That’s the whole point of being ‘undercover’; to assimilate. Tap in.

10 meters: The crouched man looks back at me. He shouts out the tunnel.

“Hold up! Couple pedestrians!” He resumes tweaking with his camera.

It seems like an act to me, like he’s trying to ignore me. I walk right up to him. “Hallo,” I say. He looks at me. I’m washed away; I see my brother. His English falls into a blackhole, as if the opening of the tunnel were a threshold into the void. Only the void is underground; the un-void is outside in the sun. Ulrik is huddled up on the threshold of life.

“Oh, I’m sorry. I don’t speak Norwegian...” Øivind sees I’m speechless and steps in. “What is going on here?”

“Oh, we’re just doing some snow-stuff.” The Ulrik look-a-like sounds jovial.

“Snowboarding?”

“Yes!” He motions to the other side of the threshold.

He looks back at me and, without thinking, I flash my badge. This draws a look of guilt over his face. Øivind pops his head into the light. It draws a huge smile on him. I have to drag my eyes off of Ulrik. One of them is directly above us on the bridge. Another stands on the stairs that lead up to the road. He has a giant piece of camera equipment in his hands. These are undoubtedly the snowboarding Americans from the dinner table. The girl walks by, smiles, and stands off to the side next to a pile of shovels.

One of them yells down at us.

“Hold up!” Ulrik yells back. He looks at me. “Would you like to watch?” I can barely nod.

“Alright, just stand right behind me.” I idle. “Yup, just back a bit.” He guides me. “Now just stay there.” He tweaks his head back into the camera. “Alright, good to go!” he shouts.

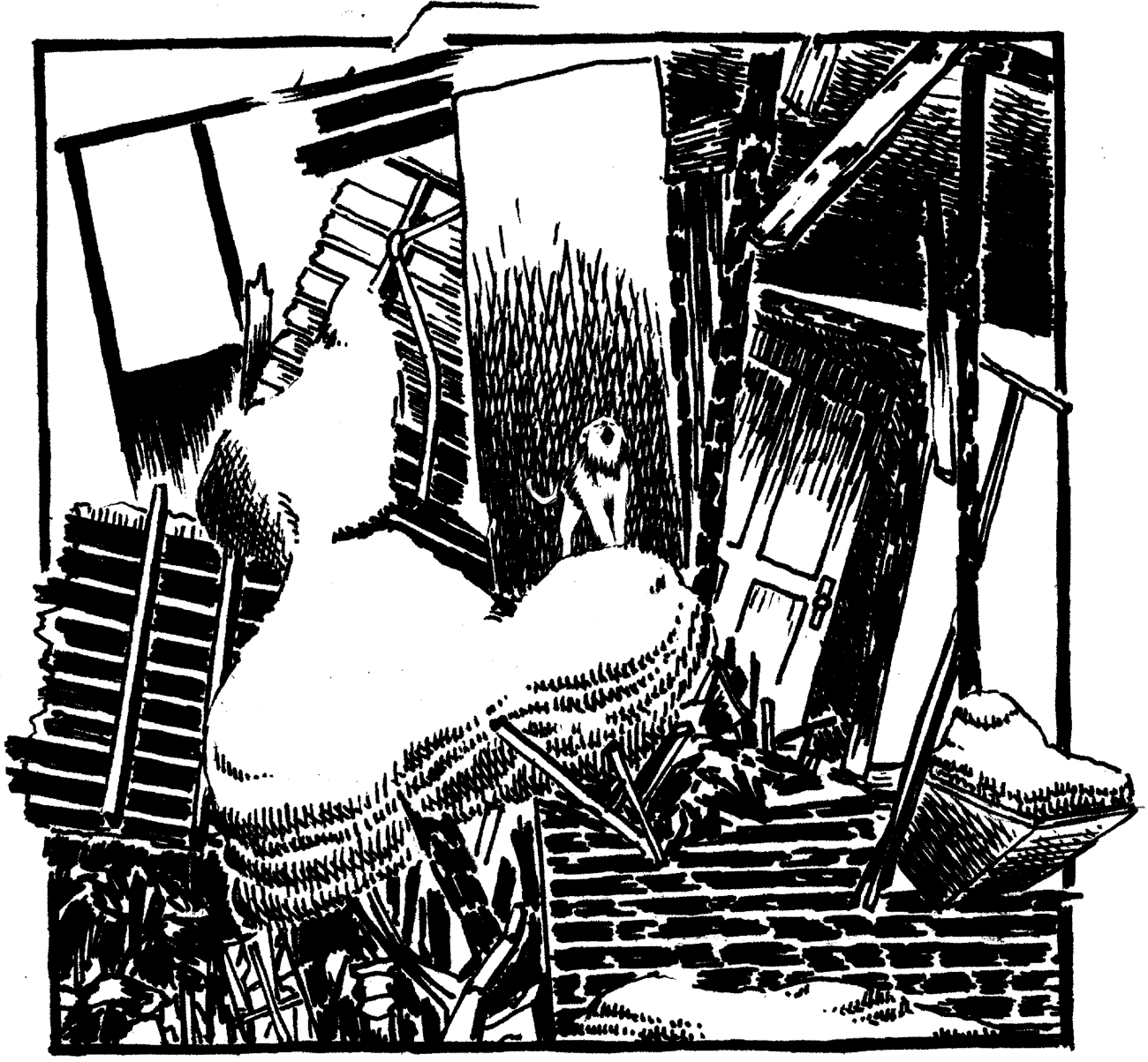

A collective stillness blankets the area. Somehow, there’s a focus on the brick wall that lines the staircase. There’s a rail protruding slightly off of it. A noise permeates from the top, but my view is blocked. The noise comes closer. It seems like everyone is holding their breath. A snowboarder appears, zooming towards the stairs. He leaps onto the railing, flattening himself against the wall. The silence is obliterated by the sound of grinding bricks. It’s incredibly abrasive yet the man is poised. A blister that’s become so calloused it’s smoothed over. Frenetic energy wearing a stone mask. Time stands still, but only for a second. He flies off the rail and lands on his feet, glides by us into the tunnel, down the strip of snow into the void. He comes to a stop, the reverberation quits, and the rest of them become animate. Cheers fall from the deck above. One of them jogs into the tunnel to hug the snowboarder.

Ulrik stands up and looks me in the eye, smiling somewhat reluctantly. He knows why. He acts coy. “What do you think?” It’s classic Ulrik. Bashfully bending the rules. I examine the whole scene. The snowboarder walks by hesitantly. He exchanges a look with the cameraman on the stairs and continues walking. It’s as if they’re using telepathy.

Then he gives himself away. He says, “Pretty cool, right?” Ulrik was not self-conscious, not in that way. This is not my brother. This is an American. A lawless cowboy of a man. I turn stiff.

“You were here last night.” His cheeks redden. “Yes.”

“In the tunnel,” I say.

“Yes. We, um… We were trying to snowboard in there.” I give him nothing in return. He squirms. His constituents watch us. Despite remaining unaffected, I sense the pressure he feels.

“But we cleaned it up. And we’ll only be here for another 10-20 minutes. And then we’ll clean all this up, too.”

“A lot of people use these stairs to access the train,” I say.

“Right – but we have spotters.” He motions to his crew. One of them is sitting on a shovel eating a sandwich. The one above us is eavesdropping. The girl is jumping rope on a dry spot in the walkway. “We’re not trying to cause any trouble. We’re just going to snowboard for a little longer, clean up, then we’ll be on our way.”

“You were at Nidarvolle skole, too.” He looks puzzled. As does Øivind – he has no idea how I know all of this.

“School – you were at the school yard.”

His mind expands and, with it, too, his eyes. “Yes. Yeah, we were at the school.” The Americans are all staring at us. Moreso at him than me.

The stillness weighs heavy. The sun shines brightly. It seems stronger today than it has in months, casting dense shadows of the two men on the stairs against the brick wall. The shadows are concise. Everything is cut-and-dry. The snow splatters from the last go already melted and dried up. The sun made them vanish. The sun vanishes everything.

The man next to me – the American, the man with the dinky camera, the man who is not my brother – looks at me with honest eyes. They’re saying ‘C’mon. No harm, no foul. Don’t kick us out. We came a long way’.

My eyes dance for a moment before landing back on him. I tuck my badge again. “Just keep doing what you’re doing.”

I can’t hear his reply, I simply nod and turn back down the tunnel. Øivind’s feet crunch on the ice behind. “So that’s it?” I roll the window down, letting the draft suck out Øivind’s question. My blinker goes on. I look left, turn right.

“No tickets. No reprimanding.”

“Nope”

“And who the hell were they? How did you know who they were? I mean, you didn’t even take down their names! And they were clearly foreigners. No passport check, no – “

“Impressive, huh?”

“Well you certainly had me fooled.”

“No, not me – them. I’m surprised you didn’t ask for an autograph.” The sun hits my cheek. I come to a stop at a red light. My face turns toward the warmth. I feel as though I may never have to run the wipers again.

“Well, yes, it was impressive. But I mean, I’m supposed to be learning from you. And it’s not like you gave me a whole lot to go off of back there. I mean, you knew who they were, for fuck’s sake! And you didn’t even tell -”

“No, you did fine.” The light goes green. “Really, Øivind. We did our job.”

“That right? I guess I’m still learning about what our job is, exactly. Clearly we’re not out to lay down the law…”

“No. No, we’re not. Not where it doesn’t need to be laid, at least.”

I can tell he’s grappling with the change in position. That’s common for someone fresh off the force. Undercovers operate differently. I forgot about that difference. Time changes things. Creates habits. Habits harden. You adhere to them. Worship them. And before long, you’re worshiping damn-near the same thing you swore you wouldn’t. And you look just like your enemies. You’re no longer controlling power, but using power to control.

Thankfully, time keeps ticking. Things can change, and change back again. The ocean can build a storm. It can also tidy up the wreckage.

I throw the car in park.

“Now what?”

“What?”

“Captain, you gotta start filling me in.”

“Wait here, I’ll be right back.” I climb out before he can ask any more questions. I dash across the street toward a second-hand store. I walk out less than five minutes later with a snowboard under each arm. Øivind’s leaning on the car, smoking. He sees me and laughs.

“Inspired?” I say nothing.

“We’re going snowboarding?”

“This one’s for my kids.” I hold up the smaller one awkwardly. “And I guess this rusty piece of shit is for me. Get the trunk, will you?”

He flicks the butt and opens the door. I cram the boards in.

“What about boots? Don’t you need special boots for those things?”

“Eh, fuck it. We’ve got snow boots at home. We’ll figure it out.”

“When – next year?” He opens his arms to embrace the sun. “Snow’s melting, buddy. Spring has sprung.”

“We’ll see about that.” I close the hatch.

“Hey Captain.”

Here we go; what’s he going to ask now?

“It’s nice to see you smiling.”

I roll my eyes. “Let’s get back to work.”